Many scholars view global civil society as evidence of democracy within emerging forms of global governance. But what are the origins of global civil society? Do these origins matter for how it might contribute to democratic governance? This paper examines two possibly competing hypotheses on the origins of global civil society. The first suggests that global civil society has been developing rationally over a long period of time, continuous with the development of domestic civil society in democracies. The second postulates global civil society to be a relatively new phenomenon, one that has emerged to respond to unprecedented challenges to democracy as a result of globalization. Drawing on a case study of global politics surrounding plant biotechnology, we evaluate these two hypotheses. Our findings support the second, more institutionalist, possibility. We then use these findings to comment on how global civil society might be defined and on its relationship to democracy.

This paper offers some initial research and reflections upon these hypotheses. Using a case study of political activity in the area of plant biotechnology, we find evidence that indicates that the second one — focused on the novelty and recent origins of global civil society — is more credible. Not only is the formation of a transnational policy space in this area quite recent, but also the dominant organizational form in the space tends toward networks — networks, in turn, that appear to be responding to intense pressures to be more globally extensive. Its politics are highly contentious and by no means confined to the rational voluntary action emphasized by the first hypothesis.

We organize our presentation of the evidence for this argument in the following steps. First, we outline the arguments about the origins of global civil society. Second, we offer a working definition of "non-territorial governance" and assess its implications for democratic politics. Third, we present briefly the emergent transnational policy space for plant biotechnology, outline the principal spheres of authority in the space, and note the intense, highly contested nature of politics involved. We then describe the organizational characteristics of key civil society actors present in the space, noting the dominance of the network form and the strong recent pressures for global extensity. In the last section of the paper, we return to the concept of global civil society, make some suggestions about ways it might be defined, and comment on its relationship to democracy.

The Origins of Global Civil Society

Two somewhat competing perspectives have emerged on the origins of global civil society and these perspectives, in turn, can be linked to differing views of the novelty of contemporary globalization. A first view would see global civil society as an arena of political activity that has grown gradually and continuously since the mid-nineteenth century, with perhaps some acceleration in the period after 1945. Boli and Thomas make this argument most persuasively, arguing that a world culture and a world polity have emerged over this period. In their words, the world has come to be "conceptualized as a unitary social system, increasingly integrated by networks of exchange, competition and cooperation, such that actors have found it 'natural' to view the whole world as their arena of action and discourse" (1999, 14). They add that this world polity is constituted by a world culture, "a set of fundamental principles and models, mainly ontological and cognitive in character, defining the nature and purposes of social actors and action"(ibid., 18). This culture is global, Boli and Thomas argue, in that it is cognitively constructed in similar ways throughout the world and because it is held to be applicable anywhere in the world.Boli and Thomas (1999) seek to unpack the elements of world culture by investigating the characteristics and operations of international non-governmental organizations (INGOs). This investigation yields five dimensions of world culture:

In this view, global civil society emerges gradually as INGOs come to interact more frequently and in greater numbers with states and over time with intergovernmental organizations (IGOs). In its basic components, it is the extension of European Enlightenment principles to a world stage and is constituted by the Western institutional innovations of the nation-state, law governing inter-state relations, and the voluntary association. In this respect, it stands as the global equivalent of domestic civil societies in Western democratic nation-states. Where conflict occurs in global civil society, it will be of the familiar form involving rationalistic arguments and competing sets of information.

This line of argument parallels that of many globalization sceptics who argue that contemporary globalization is not new or unique. Rather, it is the product of a long process of internationalization that began in the nineteenth century. Developed most eloquently by Hirst and Thompson (1999), such sceptics suggest that current levels of international activity are not historically unique and that arguments are exaggerated when pointing to new forms of global corporations and globalized production, and to a changed, weakened space of policy autonomy for nation-states.

A second view emphasizes the novelty of global civil society, seeing its development occurring primarily in the past thirty years. Several factors set the stage for its emergence. Capitalism, particularly through the integration and dominance of global financial markets, has assumed a new global form (Castells 1996). Wapner adds: "While many regions have possessed market economies for centuries, there is now a globalized marketplace in which individuals and corporations produce, transport, and sell products the world over. The globalization of markets circumscribes a domain across national boundaries in which people can interact free from complete governmental penetration and extends the experience of private economic activity" (2000, 268). In their study of global activism around world economic institutions, O'Brien et al. (2000) also note the importance of increasing economic interdependence in stimulating global civil society.

In addition, as governments have become confronted with global problems such as climate change, stability of financial markets, and the protection of human rights, they have moved to set up more and more intergovernmental organizations operating on a global scale. Drawing on his expertise on contentious politics and social movement theory, Tarrow (2001) suggests that when states create international institutions to serve their collective interest, these generate incentives for transnational activism. The needs of officials in these institutions for legitimation and for sources of information will generate still further incentives. These incentives "combine to create a transnational, activist elite that staffs international non-governmental organizations and comes together within and against the policies of international institutions" (ibid., 14). Keck and Sikkink (1998a) observe that these elites, in turn, form alliances with states, selected officials within international institutions and domestic social movements to form "transnational activist networks." They add, however, that these networks can also arise in response to states blocking policy initiatives at the nation-state level. In this respect, Keane notes "It can be argued that global civil society is also the by-product of governmental or intergovernmental action or inaction" (2003, 92). Kaldor amplifies this point by noting a synergy between states committed to multilateralism and global civil society: "The more multilateral the state, then the more it is likely to provide access to and funding for global civil society groups as a way of strengthening support for multilateralism. And the more a society is globalized and the more multilateral the government, the more favourable is the infrastructure and the opportunity for the growth of global civil society" (2003, 138).

This perspective on the origins of global civil society differs from the world culture approach in three ways. First, it puts greater emphasis on the information and communications technology revolution and its impact on social organization. Castells writes, "as a historical trend, dominant functions and processes in the information age are increasingly organized around networks. Networks constitute the new social morphology of our societies, and the diffusion of the networking logic substantially modifies the operation and outcomes in processes of production, experience, power, and culture" (1996, 469). Keck and Sikkink capture this aspect in their focus on transnational activist networks, but they are far from alone. Virtually all scholars who write about global civil society as a new phenomenon emphasize the importance of network logics.

Second, rather than seeing growing consensus on a world culture, they stress that the increasing levels of interdependence lead to greater consciousness of difference. Robertson writes, "In an increasingly globalized world there is a heightening of civilizational, societal, ethnic, regional and, indeed, individual self-consciousness" (1992, 27). Accordingly, Tomlinson, adds, globalization "is a far more complex process than can be grasped in the simple story of the unilinear advance of the West. . . . for all the superficial signs of cultural convergence that might be identified, the threat of a more profound homogenization of culture can only be deduced by ignoring the complexity, reflexivity and sheer recalcitrance of actual, particular cultural responses to modernity" (1999, 97). For these reasons, global civil society is much more likely to be populated with various forms of contentious politics and even violence, than with rational voluntarism. Moreover, differences in points of view on crucial points of debate can be particularly deep and difficult to reconcile.

Finally, those favouring the view that global civil society is a recent development stress that the period since the end of the Second World War, and particularly the last thirty years, has seen the emergence of a host of new spheres of authority that coexist with states. Rosenau hypothesizes that "spheres of authority other than states designed to cope with the links and overlaps between localizing and globalizing dynamics will evolve and render the global stage ever more dense" (2003, 294). On the one hand, this added complexity renders more urgent the need for coordination between states and between states and alternative spheres of authority. On the other hand, the global politics in which global civil society is inserted can become beset with conflicts immensely more difficult to resolve than at the domestic level, if only because of the absence of any world state able to make decisions or to organize coordination and consensus building.

In summary, these two hypotheses about the origins of global civil society differ in several key aspects: (1) the timing of its origin: less recent or recent; (2) the dominant logic of organization: voluntary association or network; (3) the pressures on organizations to be globally extensive: moderate or intense; (4) the nature of politics: rational or highly contentious; and (5) the sources of legitimacy: the product of rational voluntarism or highly contested.

Democracy, Non-Territorial Governance, and Transnational Policy Spaces

David Held observes that theories of democracy have assumed a certain congruence and symmetry between political decision-makers and the recipients of political decisions. Symmetry and congruence, he argues, occur first "between citizen-voters and the decision-makers whom they are, in principle, able to hold to account; and secondly between the 'output' (decisions, policies and so on) of decision-makers and their constituents — ultimately, the 'people' in a delimited territory" (1995, 16). Globalization confounds this connection between decisions, citizens, and territory by eroding the capacity of nation-state decision-makers to deal effectively with many of the demands placed on them by citizens. This development has led scholars to talk about the nature of non-territorial governance and the possibility for global civil society to address some of the challenges to democracy that arise from such governance.The term "non-territorial governance" is usually invoked in comparison with nation-state governance, which involves governance of an explicit territory. Scholte's work permits us to be more specific. If we use his term of "supra-territorial" as a synonym for "non-territorial," we can follow him and say non-territorial refers to relations that are "social connections that transcend territorial geography. They are relatively delinked from territory, that is, domains mapped on the land surface of the earth, plus any adjoining waters and air spheres" (Scholte 2002, 8-9). "Supraterritoriality," he adds, applies when "place is not territorially fixed, territorial distance is covered in no time, and territorial boundaries present no particular impediment"(ibid., 9). In short, following this line of thinking, non-territorial governance would refer to governance that is not fixed to a particular territory or place. Rather it applies to social actors, their relationships, and their actions irrespective of the territory or place in which they are. Territory provides no limit or no bound to acts of governance.

We follow Rosenau in defining governance — the second part of the concept. He writes that governance is "the process whereby an organization or society steers itself, and the dynamics of communication and control are central to that process" (1995, 14). "Control," he adds "consists of social relations that constitute 'systems of rule' " (ibid., 15). Such systems are in place where regular behaviours systematically link efforts of "controllers" to the compliance of "controllees." Such efforts may come in hierarchical form backed up by law or more informally through the evolution of "intersubjective consensuses." Rosenau observes a tendency toward governance that is multidirectional and a mixture of formal and informal structures. The interactions in this type "constitute a hybrid structure in which the dynamics of governance are so intricate and overlapping among the several levels as to form a singular, weblike process that . . . neither begins nor culminates at any level or at any point of time" (2003, 397).

Keohane and Nye observe that the increasing extensity, intensity, and velocity of transnational linkages that come with globalization are changing the practices of governance in the international realm: "One way to see the problem posed by globalization is that the hierarchies — both the national governments and established international regimes — are becoming less 'decomposable', more penetrable, less hierarchic. It is more difficult to divide a globalized world political economy into decomposable hierarchies on the basis of states and issue-areas as units"(2000, 30). There is a multiplication of sites of power and authority where actions in one place are not necessarily coordinated or consistent with actions in another. In fact, they may contradict one another. Under these circumstances, politics becomes less ordered, more fragmented, and perhaps more chaotic.

In this respect, we suggest non-territorial governance takes place in transnational policy spaces, generated in response to pressures by states and civil society actors to address global problems.1 The choice of the word "space" signifies that borders and boundaries for policy-making are variable and porous, and are being created and recreated in response to globalizing processes and policy developments. Not only do states "act" in this transnational space, but so also do a range of non-state actors often characterized as being part of global civil society. In these spaces, however, the symmetry and congruence between decision-makers and citizens characteristic of "territorial governance" is lost. Some analysts suggest that global civil society can help address this loss by creating direct linkages between global policy-making and citizens. Understanding the origins and characteristics of global civil society is thus important for evaluating this suggestion.

The Transnational Policy Space for Plant Biotechnology

With this understanding of non-territorial governance in mind, we turn to the politics of plant biotechnology. The genetic engineering associated with the development and commercial use of plant biotechnology involves moving the information coded in a given gene or gene sequence from one living organism to another. Unlike past efforts of this kind, recombinant DNA techniques permit this transfer of information to occur outside the bounds of place, whether defined as physical location or as species type. A gene can be removed from a living organism found in one physical location in the world and placed in another living organism that would never have had any physical contact with the first. Moreover, the species type of the second organism may be completely different from that of the first. In this respect, the information encoded in genes is able to move across supraterritorial spaces. Genetic information becomes susceptible to globalization in ways not possible in the past.Several developments related to the application of these technologies to plants, particularly plants cultivated in agriculture, have generated pressures for non-territorial governance and the creation of a transnational policy space. First, a small number of large transnational corporations based in the United States, the European Union, and Japan have controlled research and development in this area and have led the commercialization of genetically modified (GM) plants. These firms, in turn, seek to market their products globally, wherever commercial agriculture promises them a good economic return. Close to 99 percent of GM crops commercially grown in the world involve four extensively traded commodities: soybeans, corn or maize, canola (a form of rapeseed), and cotton. The United States is the largest producer and exporter of these crops, followed by Argentina, Canada, and China.

Three of these commodities — soybeans, maize, canola — are consumed directly by human beings or indirectly in a wide range of processed foods and in meat from livestock raised on soybeans or maize. Given the novelty of the technology, the lack of confidence in nation-state regulation of food safety, and suspicion about global corporations more generally, many have opposed GM crops and foods, arguing that they are potentially unsafe for human or animal consumption. In the European Union in particular, after Monsanto's herbicide resistant soybeans were approved for commercial release in 1996, political opposition has increased to the point that the European Union placed a moratorium on the import and the commercialization of any new GM crops, which is only now being gingerly lifted. Behind this dispute lie deeply set differences over the role of science in assessing food safety and over how precaution in regulation is to be implemented.

Second, aside from the worries about food safety, others have pointed to evidence that GM plants will cross pollinate with non-GM plants of the same species or potentially with other plants, particularly weeds, in the wild. The consequences of such cross-breeding are not particularly well studied as of yet, but preliminary results point to some possible losses of biological diversity. Fearing a loss of biological diversity and inadequate safeguards for protecting human and animal health, individuals and non-state actors have resisted rational voluntarism by forming interlinked transnational and national networks to demonstrate against genetically modified organisms (GMOs) and foods, to organize petitions, to blacklist GM food products on websites, and in some instances to raze fields where GM crops are being grown, whether commercially or for testing by governments with a view to commercialization.

Finally, the capacity to transfer genetic information and processes across species types and from one locality to virtually any other one raises questions about whether genes and genetic processes are a common heritage of humankind or "intellectual property" that can be patented and owned privately. These issues pit many of the governments and the relevant corporations in the countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries against the governments, local communities, and indigenous peoples of the Global South. Such issues have become tied in more directly with the trade regime with the 1994 Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) of the World Trade Organization (WTO). Similar to the politics of food safety and biological diversity, the non-state actors and developing country governments in the space focused on these issues have used a range of tactics that extend well beyond rational voluntarism.

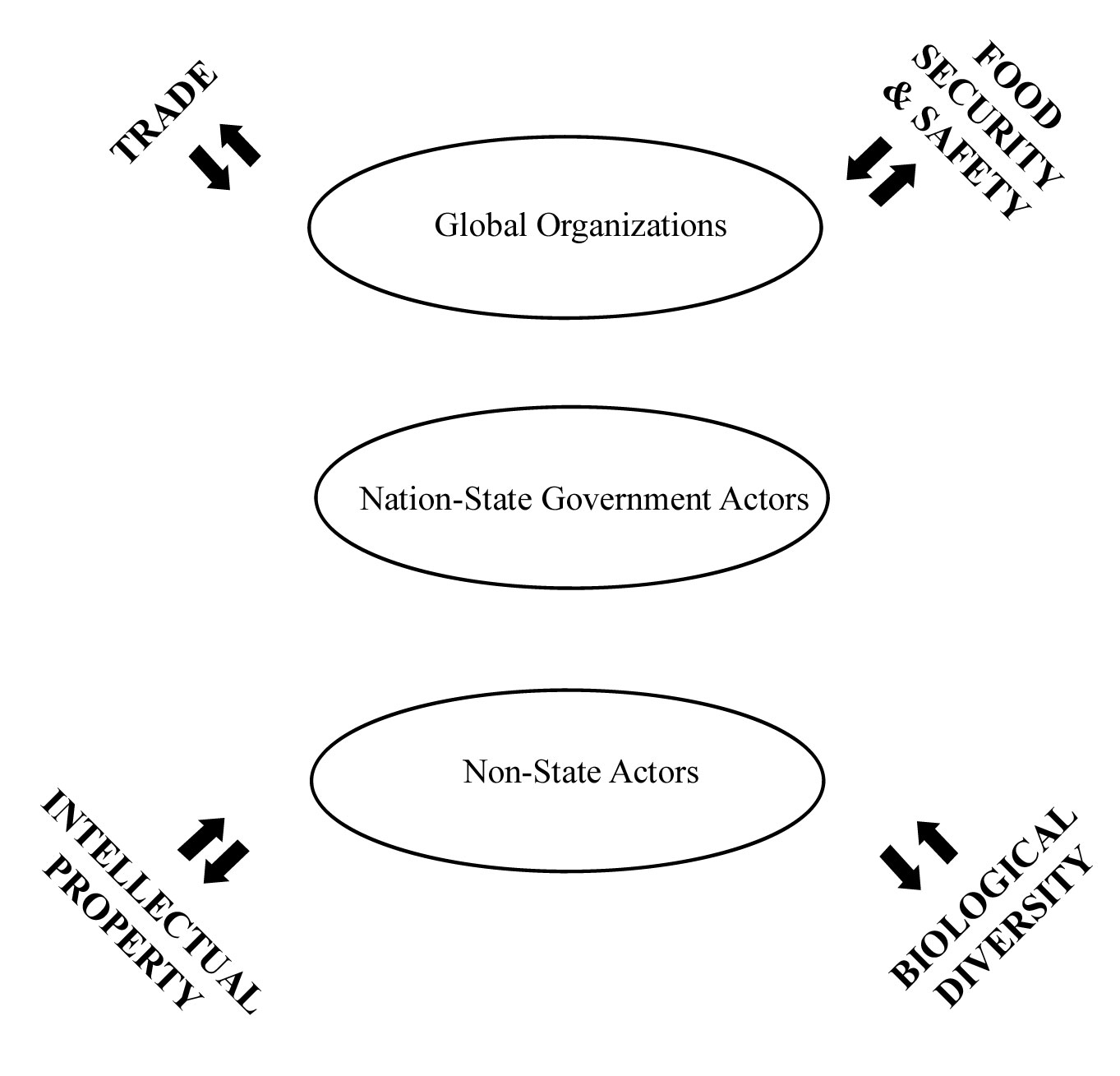

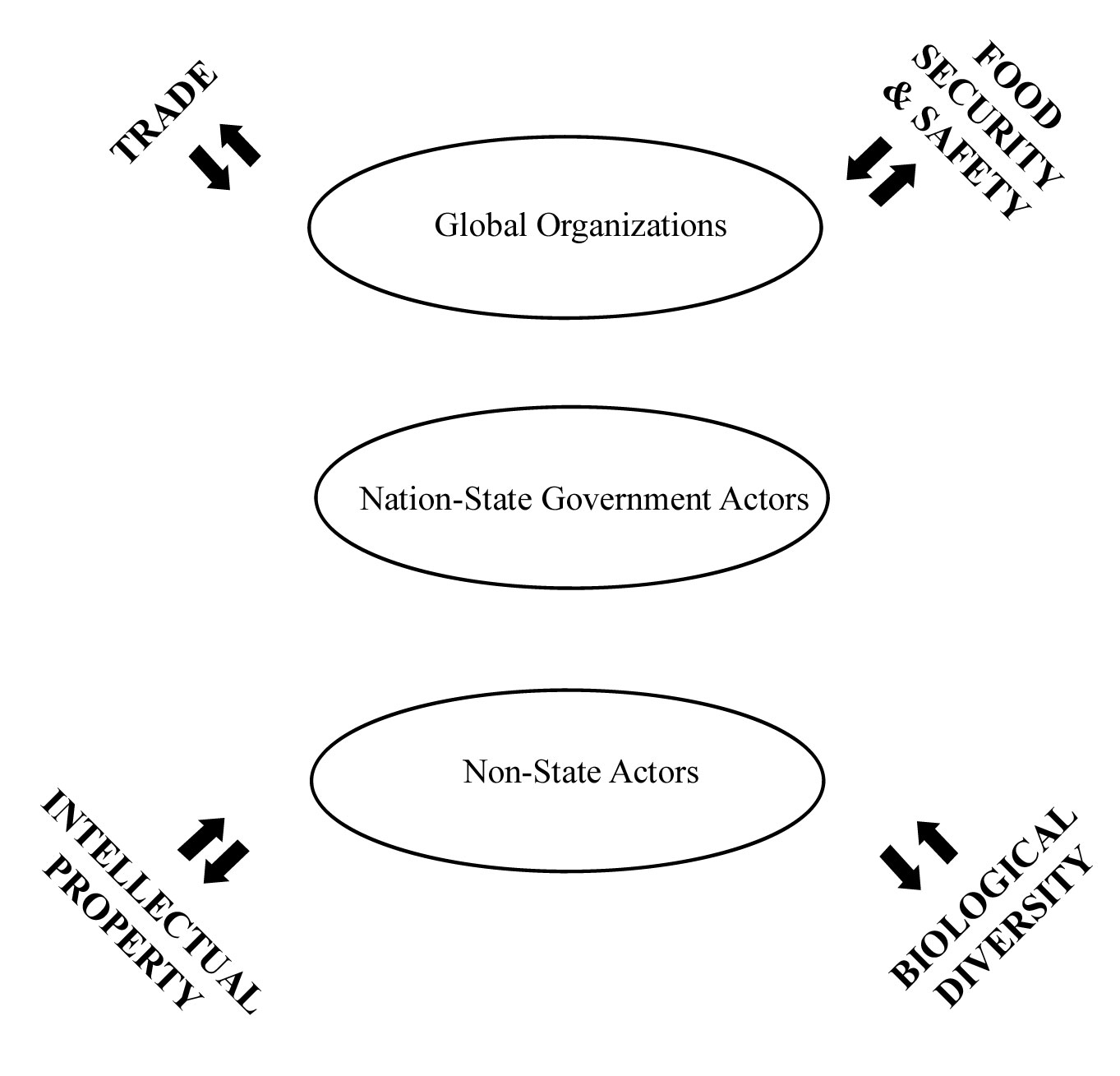

These political concerns of opponents of the technology, in combination with the global ambitions of biotechnology corporations and their supporting governments, have constituted a transnational policy space beginning in the latter part of the 1990s. This space is structured by linkages between four, sometimes competing, spheres of authority — spheres that have themselves evolved as the space has been populated (see Figure 1).2 The first sphere of authority governs international trade, with the principal site being the WTO formed in 1995. Within the WTO, the newly constituted Committees on Agriculture, Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures, and potentially Technical Barriers to Trade are the principal policy-making forums. All are classic intergovernmental bodies, with no direct participation by non-governmental organizations. Intergovernmental organizations such as the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the Codex Alimentarius Commission (CAC), and the International Plant Protection Convention (IPPC) have begun attending committee meetings as "observers."

|

| Figure 1: Transnational Policy Space for Plant Biotechnology |

The second sphere governs intellectual property rights and is directly linked to the international trade one through the TRIPS agreement of the WTO, itself taking effect in 1995. Part of the agreement created a Council for managing this agreement and the policy issues surrounding it. The World Intellectual Property Organization, a specialized agency in the United Nations system of organizations, also plays a role in this policy area. Neither the international trade nor the intellectual property rights areas provide much formal recognition of global civil society organizations. Such organizations must place pressure on these organizations through member governments for the most part.

The third sphere of authority serves to govern food security and food safety and centers on policy flows that emanate from, and are directed toward, the FAO and the World Health Organization (WHO). When it comes to plant biotechnology, two subsidiary organizations of the FAO and WHO, the CAC and the IPPC, have assumed more important roles since the late 1990s. Both of these intergovernmental bodies are recognized in the new Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (SPS) Agreement of the WTO as international standard setting bodies. This recognition has given them an important role to play in resolving key questions about how risk assessment is carried out, the place of the precautionary principle favoured by the European Union, and how foods with GM ingredients should be labelled. The FAO also provides the umbrella for the Commission on Plant Genetic Resources for Agriculture and Food (CPGR). This commission is concerned with preserving genetic resources, whether on site (in situ) or in special collections (ex situ). Since 1983, the Commission was the host for the International Undertaking, an agreement setting out policy for preserving genetic resources as a common heritage of humanity. This agreement was revised, updated, and then approved by the FAO in November 2001 with the new name, the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture.

The philosophy behind this treaty provides a direct linkage to the fourth sphere of authority overseeing the conservation and sustaining of biological diversity, whose principal site of governance is the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) signed at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992 and its associated Conference of Parties. The CBD is also host to an international agreement on biological security, the Biosafety Protocol, signed in 2000. The Protocol came into effect in 2003 when the requisite sixty-five countries had ratified it. The Protocol sets out procedures to protect states' environments from risks posed by the transboundary transport of living modified organisms (LMOs). "Living modified organism" means any living organism that possesses a novel combination of genetic material obtained through the use of biotechnology. Both the food safety and biological diversity spheres permit more official participation of non-state actors in policy formation.

The formation of the transnational policy space accelerated considerably after the signing of the Convention on Biological Diversity, the WTO agreements on Agriculture, Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures, and intellectual property in 1994, the entry of genetically modified soybeans into the European Union market in 1996, the signing of the Biosafety Protocol in 2000, and the new treaty on plant genetic resources in 2001. As anticipated by the second hypothesis on the formation of global civil society, these institutional developments spurred the activism of non-state actors and the formation of networks, particularly as they responded to deeply set political differences on plant biotechnology.

By the beginning of 2000, two spheres of authority in the policy space had emerged as centers of deeply conflicting policy positions related to plant biotechnology. The first is centred on the international trade system and includes the WTO, food security organizations like the CAC and IPPC, and intellectual property rules found in TRIPS and the agreements overseen by WIPO and the International Union for the Protection of New Plant Varieties (UPOV). The second clusters around the CBD, its associated Biosafety Protocol, the International Undertaking revised in 2001, and the CPGR. Behind this competition lie power blocs led by the United States, focused on the trade regime, and the European Union, which favours the CBD position in key areas. The United States Congress has never ratified the CBD. Developing countries often find that neither the United States nor the European Union take much account of their concerns in their disputes with one another. Rather, they use political pressures to try to press them to take one side or the other.

Three areas of conflict between these poles are particularly pronounced.3 First, there are important differences between the United States and the European Union over the use of precaution in assessing the risks to human health from GMOs. A second area pertains to the flexibility of intellectual property rights in accommodating claims by farmers and indigenous peoples in developing countries for benefits from the use of plant genetic resources. The third area concerns the relationship between liberalized trading rules and restrictive trade measures permitted in pursuit of biodiversity objectives under such multilateral environmental agreements as the CBD. Consistent with theories that emphasize the intractability of differences that emerge in the complex connectivity of contemporary globalization, these conflicts not only appear insusceptible to resolution through rational voluntarism, but also they raise questions about the very concept of "rational progress" at the heart of the first "world culture" hypothesis.

Organizational Change and Non-State Actors

The preceding section has argued that global civil society as it bears upon the governance of plant biotechnology has neither emerged in a long gradual process nor been restricted to political activity that conforms to world culture norms and rational voluntarism. It has been constituted by a complex institutionalization of new spheres of authority at the global level and the highly contentious politics that has emerged from governance initiatives of states and these sites of authority. If the second hypothesis on global civil society formation is to be credible, we should also see non-state actors present in the policy space assuming a network form as they engage in governance. Moreover, the globalizing dimensions of plant biotechnology should push them to increase the global extensity of their membership domains.Given the range and scope of potential non-state actors with interests in plant biotechnology, it is difficult to assess how many are active in the policy space. Some of these will be national organizations, possessed of sufficient resources that they are able to participate in nation-state politics and global politics. Others are transnational, including corporations, interest associations, and social movement organizations. Based on extensive interviews with government officials and non-state actors active on plant biotechnology issues, we learned that four subsets of actors are particularly central to the space: (1) agricultural producers or farmers, the principal users of the technology; (2) biotechnology companies, the developers and sellers of the technology; (3) ecologists, the main source of opposition on biological diversity grounds; and (4) consumers, the most articulate opponents in terms of food safety.4 We find considerable evidence that the global organizations representing these constituencies have evolved to take on a network form and that they have made particular efforts to increase the global extensity of their membership since the early 1990s.

Agricultural Producers or Farmers

Three global organizations representing agricultural producers, but with varying perspectives, are active in the policy space. The International Federation of Agricultural Producers (IFAP) is an umbrella organization whose members include national-level general farm organizations. For example, the American Farm Bureau Federation and the Fédération nationale des syndicats d'exploitants agricoles (France) are both members of IFAP, which was founded in 1946. It speaks for the more established, larger and wealthier farmers from its member countries. Many of its members support the use of GMOs. In its early years, IFAP concentrated on setting up a working relationship with the FAO and on trying to promote international commodity agreements for wheat, coffee, cacao, and sugar. In the 1980s and early 1990s, it modified its approach to focus on the place of agriculture in regional trade agreements and ultimately in the Uruguay Round Negotiations.

With the conclusion of the Agreements on Agriculture and SPS Measures in the Uruguay Round, however, and thus the further institutionalization of the parameters of a transnational agricultural policy space, the Federation changed significantly. The number of new members increased dramatically, with the vast majority of these coming from developing countries. Data from IFAP show forty-two new developing country members in the period 1995-2001 compared to twelve new members from the Global South in the previous fifteen years. The modus operandi of the organization changed as well. In the words of its current secretary general, David King, "With globalisation, more and more issues reach the international level, and come on the table of our Federation. In order to cope with this, IFAP has had to change to operate as a network, learning from the way the NGOs help each other. We now share information, reports, experts, policy ideas, and representatives throughout the network, with the IFAP Secretariat in Paris playing the role of coordinator and synthesiser" (personal email communication, 9 September 2002).

In short, over the past ten years, IFAP has evolved from a coordinating organization for developed countries' nation-state level general farm organizations to a more globally extensive transnational organization. Its activities now put greater stress on building and facilitating networks of policy specialists that vary in focus and in membership from one policy issue to the next.

The International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements (IFOAM) came into existence in 1972 and is a peak body whose members are national and subnational organizations that represent organic farmers. Virtually all standards for organic production stipulate that genetically modified organisms are not permitted, leading the movement to become more active in opposing the technology. Only in 1986 did IFOAM hire a full-time manager and acquire permanent offices of its own. Since that time, however, it has grown relatively quickly.5 In 1990, it had ninety-three members, with 80 percent of these coming from OECD countries. This number increased to 243 by 1995, 462 by 2000, and 724 by 2003. Over the same period, the percentage from non-OECD countries rose to forty-one. By 2002, it employed ten staff persons and had members in 102 countries. It changed the name of its Board of Directors to the "World Board" in 1993 and this board consistently has representation from developing countries.

Beginning in the early 1990s, IFOAM put in place a regional structure that permits it to operate more effectively as a global actor. These regional groups cover Asia, Western Europe, Central and Eastern Europe, Latin America, Anglophone Africa, and Francophone Africa. Together these new activities support the organization's description of itself as the "coordinating network of the organic movement around the world," a description consistent with IFAP's own description of its evolution.

In response to the uneven effects of globalizing processes in agriculture and their potential to destroy long-standing ways of living in every continent, Via Campesina came into existence in 1992, taking a different, more decentered network form than IFAP and IFOAM. Rather than being a formal interest association whose members are other associations of like form at the national level, it is a network of social movement organizations. It describes itself in the following way: "This organization is used to unite landless peasants, small and medium-sized producers, agricultural workers, rural women and indigenous communities in the struggle against the globalization of the economy and consequently, the neo-liberal model" (www.ns.res.org.hn/via) . With adherents in Asia, Africa, the Americas, and Europe, Via Campesina has organized political campaigns that tie together issues related to each node of the policy space: biological diversity, intellectual property, food security, and international trade. It opposes GMOs. Its members come heavily from developing countries.

Its challenge to existing rules is anchored in a broad understanding of biological diversity. "Biodiversity has as a fundamental base the recognition of human diversity, the acceptance that we are different and that every people and each individual has the freedom to think and to be. Seen in this way, biodiversity is not only flora, fauna, earth, water and ecosystems; it is also cultures, systems of production, human and economic relations, forms of government; in essence, it is freedom"(Via Campesina 2000). It then goes on to propose that biodiversity should be the basis to guarantee food security as a fundamental non-negotiable right of all peoples. This right, it adds, must prevail over the rules of the WTO, thereby invoking the trade regime. The movement also highlights the importance of intellectual property issues as part of its alternative vision, calling for a moratorium on "bio-prospecting" — the exploitation, gathering, and harvest of genetic resources, and genetic engineering. As such, Via Campesina adds, "We oppose intellectual property over any form of life. We want to elevate to a universal principle the fact that genes, as the essence of life, cannot be owned. The only owner is the holder of that life, who lives it, sustains it, feeds and preserves it" (ibid., 3). This construction of the linkages between crucial nodes in the policy space is suggestive again of the fluidity and highly contested character of the politics in the space and the complexity of the flows of knowledge, people, economic goods, and culture.

The pattern of significant organizational changes of farmers' groups in response to the growth of the policy space is also found for biotechnology firms. Many of the larger plant biotechnology companies originated as producers of agricultural chemicals. When these companies saw important synergies between their chemicals and transgenic technologies that could produce seeds resistant to these chemicals, they moved to buy seed companies and to build biotechnology capacity. Examples of companies who followed this path are Monsanto, Bayer, and BASF. Traditionally, these companies had promoted and defended their interests at the nation-state level through interest associations representing the agricultural chemicals industry. When the word "chemicals" became a "dirty" one in the eyes of environmentalists during the 1980s, these associations changed their names, often in a coordinated fashion across states, to "crop protection institutes." They also became more active in developing a common defence of their interests by getting together at the international level under the aegis of the Global Crop Protection Association.

In response to the need for greater global coordination in the policy space, this association was reshaped into a new global organization, CropLife International, in 2002 with eight corporate members: BASF, Bayer CropScience, Dow CropScience, DuPont, FMC, Monsanto, Sumitomo, and Syngenta. It set up a "network" of regional associations: CropLife Africa Middle East, CropLife America, CropLife Asia, CropLife Latin America, the European Crop Protection Association, and the Japanese Crop Protection Association. Seven of the eight corporations which are members of CropLife International are members of each of the regional associations and sit on their boards of directors. The only exception to this pattern is Sumitomo, which belongs to the European Union and Japanese groups only. In turn, these regional associations included the long-standing national agricultural chemicals associations or "crop protection institutes." Some of these national-level groups have since renamed themselves to be consistent with CropLife International.

These eight companies are part of the broader biotechnology sector, with many of them developing the technology for uses in other areas including pharmaceuticals. At the national level, business interest associations exist to represent the whole sector. Perhaps the most well-known of these, and one that has been active globally in its own right, is the Biotechnology Industry Association (BIO) of the United States. It has not always acted on its own, however. BIO joined forces with BIOtec Canada, EuropaBIO, and the Japanese biotechnology association to form a loose global network in 1998, the Global Industry Coalition. This coalition operates on a more ad hoc basis, coming together to intervene at critical junctures with various global governing organizations.

Finally as suggested above, the plant biotechnology sector has close relationships with firms producing seeds. Two international organizations had existed in this sector for many years. The International Seed Trade Federation (FIS) was founded in 1924 and concerned itself with promoting a transparent, self-regulated international market in quality seeds. Its members included national seed trade associations, primarily from developed countries. It had a close relationship with the International Seed Testing Association, which sought to harmonize quality standards in seeds in the international market. FIS was complemented by the International Association of Plant Breeders for the Protection of Plant Varieties (ASSINSEL), founded in 1938, which represented the developers of new seeds and plants.

When the challenge to agricultural biotechnology came in the 1990s, it involved both an attempt to forestall trade in GMOs and GM foods and to revise private ownership of genetic resources through intellectual property rights. The TRIPS agreement of the WTO in 1994 added considerable importance to the International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants (UPOV), a long-standing interlocutor of ASSINSEL. Challenges both to intellectual property rights and to the trade of GMOs also came in the Biosafety Protocol, challenges already present in the CBD. In order to coordinate a response to these various challenges and to strengthen the input of the biotechnology industry on these issues in the policy space, FIS and ASSINSEL merged in 2002 to form the International Seed Federation. It committed itself to representing its members at UPOV and at the FAO particularly as it discussed intellectual property issues in the development of a new International Undertaking on genetic resources, and the CBD.

There are many ecological organizations actively challenging varying issues related to GMOs. Most of these are organized at the national level. Globally, two prominent organizations, Greenpeace International and Friends of the Earth International (FOEI) are active and they consist of international umbrella organizations networked with national-level associations.

Several loosely affiliated branches of Greenpeace, the earliest dating to 1971, formed Greenpeace International (GPI) in 1979. From the beginning, Greenpeace required effective operation across national borders in order to draw attention to environmental issues. As of April 2003, the International Secretariat of Greenpeace International employed 120 persons. Branch offices existed in thirty-eight countries, of which twenty-four belonged to the OECD. This number has been relatively stable. For example, the association had forty-one members in 1997. The OECD members remain quite constant, but the developing country affiliates fluctuate. Interviews with several national Greenpeace affiliates suggest that relations with GPI tend to be more informal than formal, with national organizations also being active at the global level.6 This mixture of roles conforms to the networked character of the movement as an interview with Greenpeace France indicates:

It is true that we have an international team that works on these questions, but Greenpeace is complex when it comes to relations between the national offices and Greenpeace International. We have an international team that works on these questions but particular persons at the national level are often drawn into the process at particular times. For example, our Swiss campaigner represents Greenpeace International at Codex and Jean [pseudonym] from France knows the biosafety dossier well and he takes care of all biosafety issues at the international level, including the Biosafety protocol.7

If anything, FOEI has even more of a network structure than Greenpeace and it has been more successful in developing a globally inclusive membership base. It was founded in 1971 by four organizations in Sweden, France, Britain, and the United States. This highly decentralized organization did not set up an International Secretariat until 1981, but then formed an Executive Committee in 1983 to oversee management between meetings of the then twenty-five member organizations. In the ensuing period, there has been an intensification of transnational organizing. In 1985, Friends of the Earth Europe was set up, with an office in Brussels. In 1994, members of FOEI decided to develop a common "agenda" and intensify cooperation between national-level FOE branches. As of April 2003, FOEI had become a federation of sixty-eight autonomous national member groups with a core staff of fifteen professionals at its International Secretariat. OECD countries count for twenty-six of these members, indicating that FOEI has more bridgeheads into the Global South than does Greenpeace. In its own history, FOEI reports that its global reputation was solidified in the 1990s, as it faced ever more global social and environmental issues. During this period, its membership in non-OECD countries grew rapidly (www.foei.org/about/25years.html) .

Consumers are drawn into the policy space through their concerns about food security and food safety, including risk assessment, and how these issues are affected by the rapid increase in global trade of processed foods. The consumption of GMOs and foods with GM ingredients and the trading of these commodities have accentuated consumer interest in risk assessment and in the transparent labelling of foods. Some consumer organizations at the national level such as those in France have taken relatively strong positions against GMOs. Others, including those in Canada and the United States, do not challenge the technology per se, but do emphasize the "consumer's right to know" and accountability through labelling.

A number of these national organizations in the OECD countries founded an international body, the International Organization of Consumers Unions (IOCU) in 1960. It shortened its name to Consumers' International (CI) in 1995. Unlike the ecological organizations, the organization globalized in significant ways in the 1970s and 1980s. As early as 1964, the organization noted the need to create and strengthen consumers' organizations in the developing countries (Gaik Sim 1991). In 1974, it had grown sufficiently to set up its first regional office, the Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific. During the 1980s, IOCU pushed hard on organizing in Latin America, creating a regional office in Montevideo, Uruguay, in 1987. It also expanded in Africa.

The more global structure of the consumers' movement conforms to both hypotheses about global civil society formation. It appears to have grown in the gradual way expected by the world culture hypothesis, although its founding is relatively recent. At the international level, its activities tend to conform to the rational voluntarist model, although national-level organizations, especially in the European Union, have followed a more contentious approach. Consistent with the second institutions-based hypothesis, growth also appears to coincide with increased support from intergovernmental organizations, particularly the United Nations, which gave it full consultative accreditation in the 1970s. IOCU used this status and ten years of work to secure the publication of the UN Guidelines on Consumer Protection in 1985 (Gaik Sim 1991). In the 1980s, it began to enter more and more into network arrangements, working with new social movement organizations focusing on pesticide use, high prices of prescription medicines, and tobacco advertising.

Accordingly, when the transnational policy space for plant biotechnology merged in the 1990s, the consumers' movement already had an efficacious structure in place to accommodate the change. It experienced its strongest decade of growth in members in the 1990s. By 2002, forty of its full member associations came from the OECD countries and forty-nine came from outside the OECD. Of the forty OECD members, only nine were formed after 1990, whereas twenty-four of the non-OECD members came into being in the 1990s. In January 2002, CI launched its Food and Nutrition Programme with an objective of "ensuring safe, secure, and nutritious food for all." The program consists of four themed modules: food security, food safety, biotechnology, and sustainable food production and consumption. According to CI, the program will monitor international decision-making bodies and global agreements in these areas, in addition to providing consumer education and information.

This analysis of a number of non-state actors central to the policy space for plant biotechnology shows each of them has come to utilize more of a network organizational form in the 1990s. In addition, each with varying degrees of success, has taken steps in the same period to ensure a broader participation of members from the Global South. We recognize fully the dangers of generalizing from a single case study. Nonetheless, this analysis does raise questions about the credibility of the world culture hypothesis. In doing so, it joins the research on policy areas like human rights, the environment, violence against women, and global justice, which see global civil society as a new phenomenon. It has emerged in response to states' attempts to institutionalize particular trajectories for globalization and represents an intricate web of non-state actors deeply divided over the merit of those attempts.

In reflecting upon the findings in this paper, we offer three concluding points. First, the formation of global civil society in the policy space for plant biotechnology appears to follow a two-stage process. In the first stage, several spheres of authority emerge around governance of international trade, biological diversity, food security and safety, and intellectual property. Governments play a key role in the emergence of these spheres of authority but we know as well that civil society actors will have pressured them to act in each sphere. Once created, however, with conflicting principles and norms institutionalized to varying degrees in each sphere, thereby drawing support from some non-state actors but not others, the policy space takes on a life of its own. In the process, the interchanges between the spheres of authority create significant incentives for the growth of global civil society. Such growth promises to be robust and longer-lasting. It is not simply the mobilization of various social movements around a key event like the Seattle Ministerial meeting of the WTO in 1999.Second, our data suggest that some non-state actors may respond to these incentives more strongly than others. For example, the plant biotechnology industry and ecologists' organizations changed to different degrees. The eight dominant biotechnology corporations reorganized their interest representation by giving CropLife International a new focus, linking it to regional organizations where the corporations also sit on the given boards of directors, which, in turn, link to domestic representatives. This plan gives the corporations concerned a global network where they can respond quickly to challenges to their technology on a regional and a national level. Greenpeace changed much less, and it is still heavily anchored in OECD countries. Friends of the Earth International did increase its representation in the Global South significantly in the 1990s, but its international secretariat remains small and it has not developed a regional capacity, with the exception of the European Union. Such patterns are similar to those on the domestic level where business interest associations tend to be much more strongly resourced than public interest bodies representing ecologists, consumers, women, and so on.

Third, the biotechnology industry's strong organizational response to global activism by peasants, ecologists, and consumers, among others, raises a question about definitions of global civil society. Scholte defines it "as a political space, or arena, where voluntary associations seek, from outside political parties, to shape the rules (formal and informal) that govern one or the other aspect of social life" (2003, 11). We find this definition helpful and it is similar to those offered by Wapner and Kaldor who see the key actors to be associations. All three authors stress the diversity of global civil society and caution that it is not populated simply by politically progressive organizations. However, all three would exclude market actors — including transnational corporations — from their definitions, arguing that these organizations' primary objective is making profits, rather than negotiating new social contracts (Kaldor 2003) or "cordiality" — "voluntarily experiencing the virtues of sociality and self-consciously representing oneself in a group in a social context" (Wapner 2000, 266).

In the case study in this paper, biotechnology corporations did tend to conform to these constraints, at least on the surface, by rebuilding their own organization, CropLife International, in a networked, more globally extensive form. We suggest, however, that it would be naive to think that global corporations like Monsanto or Bayer LifeScience are not themselves active in a political space seeking to structure the policy trajectory for the technologies which they own. Research at the nation-state level shows that such corporations usually have "political affairs" divisions that advocate directly for the political interests of these firms, all the while working behind the scenes in associations (see for example, Grant 1984). They are similarly active in global policy-making. Keck and Sikkink argue: "To understand how change occurs in the world polity we have to understand the quite different logic and process among the different categories of transnational actors" (1998b, 210) To fail to do so, they add, would be to "eliminate the struggles over power and meaning that . . . are central to normative change" (ibid). We conclude that understanding the logic and ways of political advocacy of transnational corporations must be every bit as important to studying global civil society. To look only at associations, or even more restrictively at social movements, would be to miss a crucial part of potential disparities in influence and power in global civil society.

Globalization's challenge to democracy results from the destabilization of the long-standing linkage between the territorial nation-state and democracy. Once authority migrates to new spheres beyond the control of any one state, thereby necessitating cooperation between states and a more global civil society, the realization of democracy becomes problematic. Confronted with this problem, many scholars have postulated the importance of global civil society in advancing democracy at a global level. This argument is an important one. Based on our analysis of policy-making in one transnational policy area, however, those making this argument need to take a careful look at how global civil society is constituted. As in civil society at the domestic level, corporate actors with concerns about profit will be present, whether directly or through interest associations. To think otherwise is naive and to misjudge the depth of the challenges to more democracy in global politics.

1. This thinking on a transnational policy space is elaborated further in Coleman (2005).

2. These nodes of the policy space are derived from the analysis in Coleman and Gabler (2002).

3. More detail on these conflicts is available in Coleman and Gabler (2002).

4. Interviews were carried out in Australia, Canada, France, Germany, and the United States, as well as at the European Union level and the global level in Geneva between 2001 and 2003.

5. The following data were all culled from successive annual reports of IFOAM.

6. Interviews were conducted in 2002 with Greenpeace national organizations in Canada, France, Germany, and the United States.

7. Confidential interview, Paris, December 2001. Translation by the authors.