Monetary Power and Political Autonomy: Exchange Rate Policy-making in Follower States

Louis W. Pauly, University of Toronto

Preface

A key question in studies of economic globalization is how much political autonomy

do smaller states, dependent on larger economic powers, have in devising a monetary

policy that fits well the needs of their citizens. In looking at this question,

Professor Louis Pauly answers: "More than you might think." He takes as his

starting point a crucial policy area: foreign economic policy as it bears upon money

and exchange. He selects two countries, so-called follower states, whose economies

are tightly linked, if not dependent, on major economic powers: Canada and Austria.

Canada's economy is highly interdependent with that of the United States; currently

over 85 percent of Canada's foreign trade is with this one country. Austria has

long been closely tied to Germany's economy.

In a careful review of the foreign economic policies of these two countries in the

era since the end of the Second World War, Pauly demonstrates that both countries

were able to pursue monetary and exchange rate policies that demonstrated political

autonomy. Here autonomy means the capacity to construct policy buffers between

itself and the dominant state that permitted the follower state to pursue interests

that reflected its own needs and those of its citizens rather than those of the

dominant state. In making this argument, Pauly also draws linkages between monetary

policy and varying forms of capitalism, the so-called "varieties of capitalism"

literature. This innovative linkage extends this literature well beyond the areas of

industrial and technological innovation policies which have been its focus. Pauly's

argument thus continues a consistent line in his decade-long research on economic

globalization, one that argues that states, even follower ones, have considerable

policy instruments at their disposal to shape globalization. They are far from

helpless.

William D. Coleman, McMaster University

Common sense suggests that successful leaders need willing followers. Coercion can

sometimes be effective, but even the most inexperienced parent soon learns the

lesson that results achieved through unforced acquiescence tend to be better and

more enduring than those achieved through the application of brute force. Political

theorists typically focus on the concept of legitimacy when they evoke the quality

that transforms raw power into something more acceptable to its target. Clearly

implicated by that concept is another one, even more difficult to measure: respect

for the ultimate autonomy of the target. In an era of rapid global transformation,

when the exercise of great power is readily observable, research nevertheless

proliferates on the meaning and nature of independence, of sovereignty, and of

political autonomy

(Grande and Pauly 2005).

In the international monetary arena, the tendency to concentrate analysis on leading

states and the shifting landscape of systemic power underplays the important matter

of ultimate limits on that power and obscures the enduring quest for autonomy among

follower states. A common assumption, certainly among international economists, is

that all follower states really want from monetary leaders are reliable monetary

anchors, external bulwarks against inflation. As long as the leader provides

stability, the acquiescence of followers is assured. Even if we accept such

reasoning as a starting point for analysis, however, it fails to capture the essence

of observable leader-follower dynamics in the monetary arena.

Despite the integrative effects of economic globalization, few follower states have

ever demonstrated a willingness simply to trust systemic leaders to do the right

thing, to carry through with macroeconomic policies that would automatically promote

and defend interests beyond their own. At the heart of the international monetary

system since 1945, indeed, follower states have typically insisted on taking out

insurance. Sometimes, this has taken the form of participation in collaborative

institutions, where the costs of a policy mistake by a leader can be widely

distributed. At other times, however, follower states have simply constructed

policy buffers under their own control. The most common buffers took the form of

exchange rate regimes and a range of policies affecting the inward and outward flow

of capital.

During the past few decades, as most follower states moved decisively to open their

economies to freer capital movements, a striking divergence developed on the

exchange rate issue. Although no follower states explicitly abandoned the idea of

political autonomy, some opted to combine capital liberalization with exchange rate

floats, while others chose hard pegs. Those inside Europe's monetary union chose

the most rigid form of pegged rates, while also choosing to work collaboratively to

manage their mutual relationship with the US dollar and other reserve currencies.

What explains these different choices?

This paper rests on the assumption that decisions taken in this regard reflect the

deliberate crafting of buffers between followers and leaders, or about efforts by

the weak to constrain the monetary power of the strong. The empirical evidence

presented in the paper will demonstrate the plausibility of this assumption, but its

more rigorous presentation is aimed at probing the reasons behind the choice of

floating or fixed exchange rate regimes among important and similarly situated

follower states at the core of the contemporary international monetary system.

Taking its cue from burgeoning contemporary research on the varieties of capitalism

in the post-1945 period, the paper advances the argument that liberal market

economies tend toward floating exchange rate regimes, while coordinated market

economies tend toward fixed regimes. In the end, such an argument turns on the

prior absence or presence of internal political mechanisms capable of managing the

domestic costs of adjustment to economic forces determined more by leading states

than by follower states themselves.

National Policies and International Monetary Order

I suspect that many economists and most international business people believe the

following: monetary order since World War II has been shaped most directly by a

shifting but generally shared ideological consensus among leading states and a core

group of followers and by the raw power of status-quo-oriented financial elites in

states capable of disrupting the system. Such a view, however, confronts plenty of

evidence of the continuing impulse toward autonomy in both leader and follower

states and of their collective sensitivity to bearing what they themselves perceive

to be disproportionate costs of adjustment to external monetary and financial

disequilibria

(Helleiner 2003). In short, we need something else to account for the

fact that, despite brief episodes of disorder, monetary power was somehow rendered

more or less authoritative in the post-World War II era. At least at the core of

the system, and lately far beyond that core, follower states have accepted as more

or less legitimate the monetary power of system leaders (

Kirshner 2003;

Andrews,

Henning, and Pauly 2002). To use Cohen's terminology, even dramatic changes in

monetary arrangements since 1945 appear to have been perceived as norm-governed

(Cohen 1983). Why did monetary followers follow? How did they reconcile their

desire to maintain autonomy with their pursuit of prosperity through increasing

economic openness? What accounts for continuing diversity in the policies aimed at

that reconciliation?

Policy buffers seem necessary to encourage followership. Of course, conventional

economic thinking may be sound: responsible macroeconomic policies in leader states

will instill confidence and trust in the system. Since such responsibility cannot

be guaranteed, however, follower states appear to insist on maintaining a meaningful

degree of political autonomy within that system. In essence, the ultimate political

contest is over the distribution of the burden of adjustment in an integrating

economic system. Just as safeguards are widely assumed to have made serious

international trade agreements possible during the post-1945 years, the

transformation of monetary power into monetary authority seems logically to have

relied on the existence of limits on the ability of powerful states to shift

adjustment burdens onto less powerful states or to determine how such burdens would

be redistributed inside those states. Unlike much weaker states in the periphery

incapable alone of spawning systemic disorder, follower states at the core of the

system could not easily be coerced (Kirshner 1995). The principled acceptance of

"symmetry" in the process of adjustment was probably never enough to ensure their

willing acquiescence. The external monetary policies of key follower states seem

instead to have been driven by diverse and effective responses to their own

perceptions of vulnerability in a hierarchically ordered system (Cohen 1998; 2004).

An obvious hypothesis suggests itself: follower states at the core of the system

were able to accept international monetary arrangements dominated by leading states

because they ultimately succeeded in constructing autonomous mechanisms capable of

defending their real economies if and when external conditions changed. Such

mechanisms likely always had the same political purpose, even if they differed quite

substantially in form: gaining as much as possible from economic openness without

compromising ultimate political independence. Of course, this is simply another way

of describing the condition long ago dubbed "complex interdependence" (Keohane and

Nye 1977). The real puzzle is why, even when the financial and monetary aspect of

that condition at the core of the system approached deep integration by the dawn of

the twenty-first century, strikingly divergent buffering mechanisms remained readily

observable. The most relevant body of scholarship suggests an answer, even if few

of its advocates have attempted to extend its insights directly to the study of

international monetary power.

Comparative political economists have in recent years convincingly excavated the

enduring foundations for variety in the styles and structures of capitalism, even in

the face of a rapidly globalizing economy. Those same foundations, the

historically-rooted internal arrangements that still constitute national political

economies, seem plausibly to explain the striking diversity in external monetary

policy choices. Such an argument might resolve an empirical puzzle confronting

those of us simultaneously interested in the international politics of money and the

comparative politics of economic adjustment. To be more specific, in the advanced

industrial world — or what I called above the core of the system —

some key follower states resolutely opted for a floating exchange rate regime

vis-à-vis their major trading partner during most of the past sixty years,

while others have just as resolutely opted to peg the value of their currency to

that of their main trading partner. This stark and continuing difference correlates

well with the distinction contributors to the "varieties of capitalism" literature

make between liberal market economies and coordinated market economies (see, for

example, Kitschelt et al. 1999; Hall and Soskice 2001; Hancké and Soskice

2003). Such a distinction, in turn, centers mainly on idiosyncratic arrangements for

wage bargaining and, more generally, for redistributing internally the net benefits

and costs of ever-deepening national involvement in external markets. In short,

certainly since the early 1970s, Anglo-American systems appear to have relied on

floating exchange rates, while continental European and many Asian systems have

preferred pegged or even fixed regimes. Is it possible that more than correlation

is at work here?

One way to address such a question is to take two significant follower states with

long histories of choosing different policy paths and to uncover the reasons their

own policy-makers used for doing so. The balance of this paper does precisely that

by selecting Canada as the perennial currency floater and Austria as the exemplary

fixer. Surprisingly few comparative studies of these follower states exist.1 On the surface, they

each have similarly asymmetrical (and dependent) economic relationships with their

larger neighbours and main trading partners, the United States and Germany

respectively. Under the surface, they have similarly complicated and historically

fraught political relationships with those same states. Still, they have typically

made starkly different choices in the monetary arena.2

As Helleiner (2003) notes, prominent international political economists predict that

currency politics in small, open economies will incline in the direction of exchange

rate stability (see also Frieden 1996; Henning 1994). Despite rapidly increasing

levels of integration with (and dependence on) the United States when it comes to

trade and investment, however, Canada confounded such expectations as it jealously

guarded its national currency and maintained a floating exchange rate for all but

thirteen of the years since 1945. It continues, moreover, to reject the logic of

monetary union. In contrast, facing high levels of economic dependence on Germany,

Austria has long followed the opposite path.

As we examine the reasons for this difference, we are also implicitly exploring the

limits of international monetary power. The two case histories probe the nature of

relationships between followers and leaders.3

My hunch is that to understand the

buffers within those relationships is to understand the boundaries of monetary power

in a system that remains centered on the United States, Germany, and Japan. Perhaps

soon China will join that system fully. Perhaps Russia, Brazil, and India will not

remain forever on its margins. As it has in the past, however, the prospect for

future systemic stability may well depend on the extent to which such power is

rendered into more enduring authority. To the extent it is reasonable to argue that

this depends on the existence and operation of political buffers under national

control, we had better understand the nature of those buffers and the reasons for

their continuing variety.

The Canadian Case

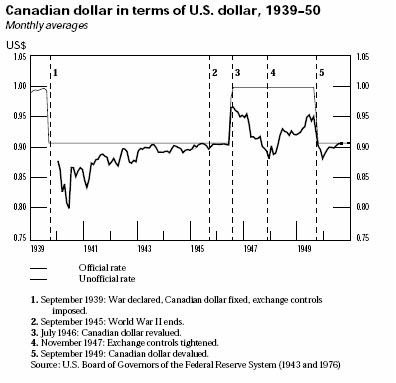

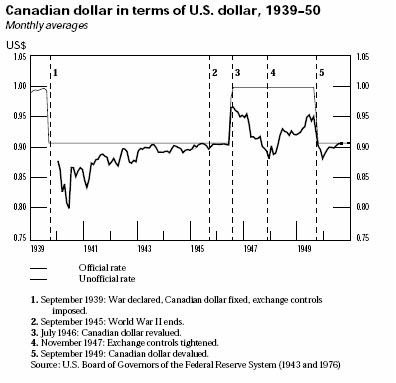

Figure 1 (Powell 1999) suggests a

straightforward story. With the significant exception of the gold standard era, of

the periods of world war, and of the anomalous 1962-1970 period, Canada has relied

heavily on the policy tool of flexible exchange rate adjustment to manage its

deepening interaction with its main trading partner. At three points in the

contemporary period, strategic moves occurred not only in actual exchange rates but

in the very nature of Canada's exchange rate regime. In 1950, it broke away from

its Bretton Woods' commitment by floating the dollar. In 1962, it re-pegged. And

in 1970, it returned to floating once more, a policy that continues to this day with

ever decreasing effort by the Bank of Canada directly to manage the currency's value

and, after 1991, an ever deeper commitment to targeting monetary policy simply on

inflation and hoping that movements in exchange rates complement, or at least not

entirely undercut, movements in interest rates.

|

| Figure 1 |

During the early post-World War II period, Canada's ties with Britain attenuated,

and the United States rapidly became the only partner crucial to its economic

fortunes. Since 1971, an exceptionally deep economic partnership with the United

States developed; this was finally acknowledged and even embraced in 1988 in the

Canada-US Free Trade Agreement (Pauly 2003; Clarkson 2002). At present, some 87

percent of Canadian exports go to the United States, although in the wake of

transport integration some of this huge proportion (unmeasured by Canadian or US

authorities) represents goods passing through US ports. But we need to back up a

bit if we are to understand exchange rate policy in the context of that larger,

multi-faceted relationship.

One method is to trace the rationales for the three principal changes in Canada's

postwar policy regime (Plumptre 1977; Wonnacott 1965; Fullerton 1986; Helleiner

2005). A key source is the one person who was at or very near the center of policy

decision from 1940 right through to 1973, Louis Rasminsky. Rasminsky managed

Canada's Foreign Exchange Control Board during and immediately after World War II.

He played an important role in the drafting of the Bretton Woods Agreement in 1944,

served as Canada's first director on the International Monetary Fund's (IMF)

executive board, and held the position of deputy governor and, from 1961, governor

of the Bank of Canada until his retirement in 1973. Rasminsky lived a full life,

and was into his ninety-first year when he died in 1998. I had the opportunity to

interview him in 1993 and again in 1998.

Rasminsky termed his presence at the 1942 London meeting where Keynes unveiled his

draft plan for the postwar monetary system, "the highlight of my international

monetary career."4 Like others at that meeting, he was convinced that deflation,

recession, and competitive currency devaluation would be the chief dangers after the

war ended. Keynes' ideas for "a clearing union and code of behavior based on

non-discrimination and convertibility" made a deep impression on Rasminsky, for they

promised an elegant way to avoid recapitulating the dismal monetary experience of

the 1930s. That the plan envisaged stable exchange rates was not the main

attraction, however. Rather, it seemed to chart a politically feasible and

economically sound path back to more freely flowing international capital movements.

"Non-discrimination and convertibility were so important to Canada because of the

structure of our trade then: we had a surplus of imports from the United States,

which we paid for through a surplus of exports to Britain and Europe, and some

capital inflows from Britain but mainly from the United States." Capital controls

were never welcomed for their own sake, but they proved essential during the war

years. They came off again as soon as possible, a process completed in 1951.

Although Rasminsky had a personal inclination toward the idea of exchange rate

stability embodied in the IMF, he claimed always to share with other Canadian

officials a fundamental commitment to easing conditions for international capital

flows. "We were always committed to freely flowing capital, both before then and

ever after."5 That commitment only deepened when the postwar reality became

economic boom instead of bust. With capital flows to Canada, mainly from the United

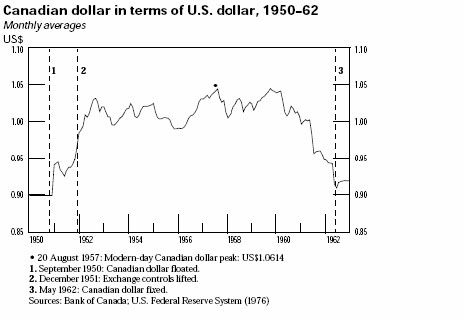

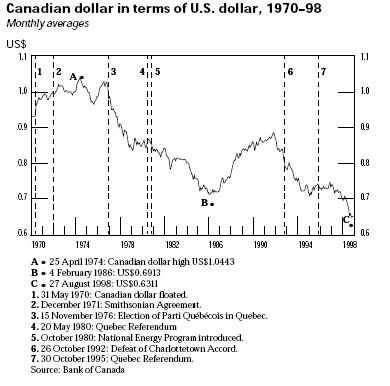

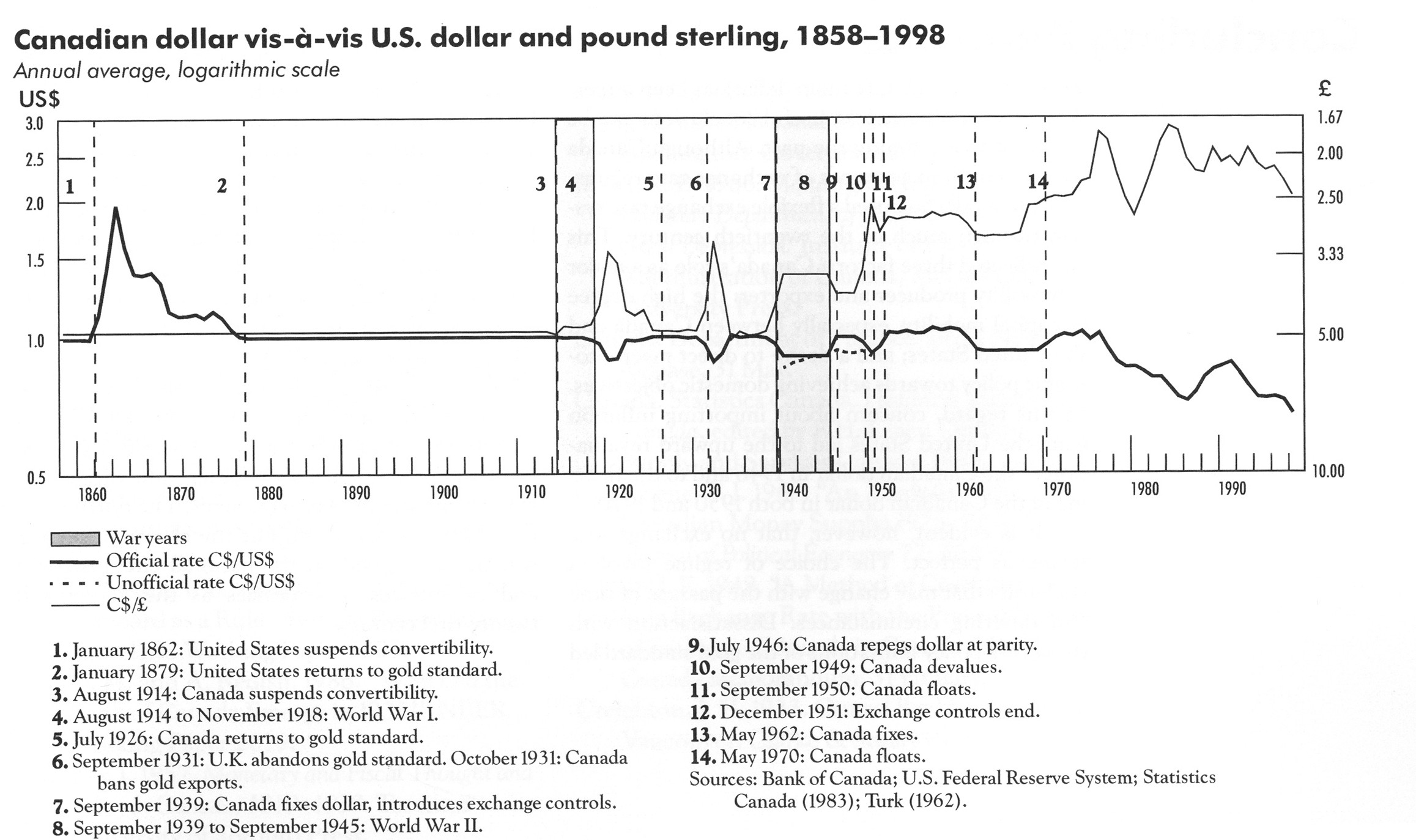

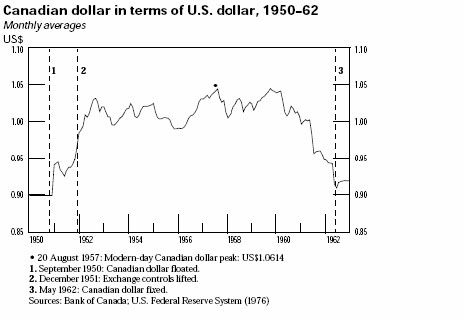

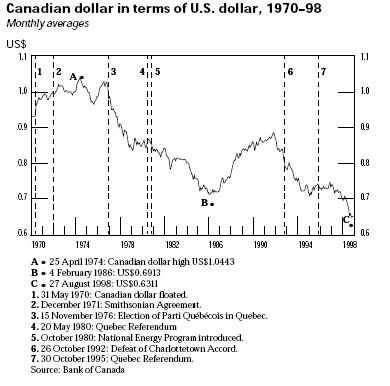

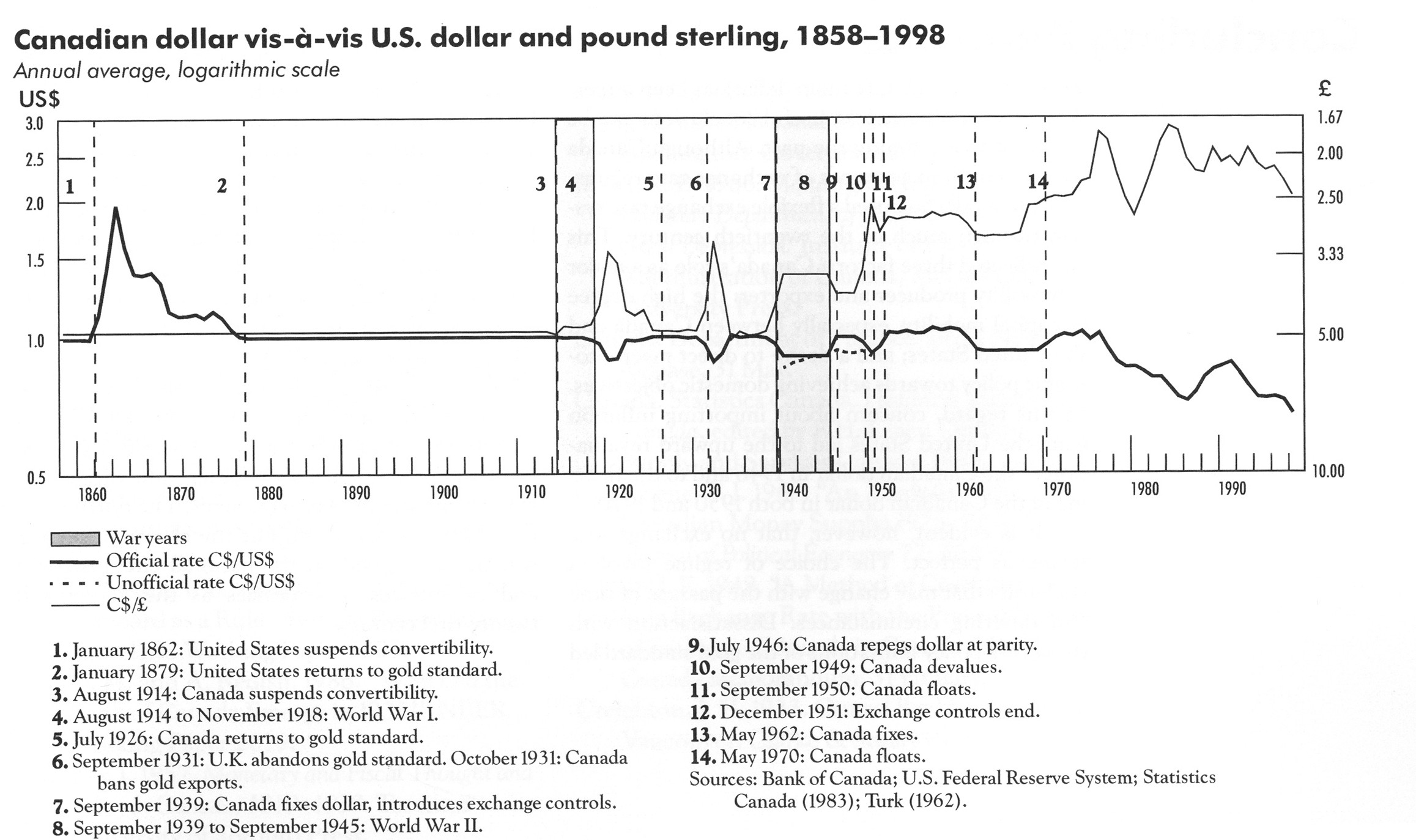

States, rising rapidly at both of the crucial turning points of 1950 and 1970, "we

were always willing to sacrifice exchange rate stability if need be." (See Figure

2, Figure 3, and Figure 4 (Powell 1999).) "We didn't relish breaching our Bretton Woods commitments in either case," Rasminsky

recalled, "but what could we do?" "When we floated, we floated up, so we could

always deny competitive devaluation."6

|

| Figure 2 |

|

| Figure 3 |

|

| Figure 4 |

Although some American counterparts understood Canada's position in both 1950 and

1970, rising tension existed at the official level, especially in 1970. For

Rasminsky, this was nothing new. He had hopes even into 1944 that something like

Keynes' politically neutral Clearing Union might succeed. In theory, such a

mechanism could have reconciled desires for both exchange rate stability and capital

mobility, and Canada could have supported it. But Rasminsky soon concluded that the

United States had no stomach for such a multilateral ideal, one which would give

voice and, more importantly, automatic and certain financing to non-Americans when

they faced balance-of-payments adjustment problems. In the late 1940s, he

complained about the niggardliness of Fund financing, and early on he worried that

the Fund was condemned by the United States to be much less relevant than it could

have been. His concern rested on his close observation of US behavior in the

crucial 1944-46 period. A remark he recorded during the 1946 inaugural meeting of

governors of the IMF and World Bank in Savannah, Georgia captured the spirit of the

lesson Rasminsky learned then and carried with him throughout his life: "We have all

been treated to a spectacle of American domination and domineeringness through their

financial power which has to be seen to be believed…US foreign economic

policy seems to be in the hands of the Treasury who are insensitive to other

peoples' reactions and prepared to ram everything they want down everyone's

throat.(Muirhead 1999, 111)"

In 1950, when Canada found itself awash in US dollar reserves, the necessary

consequence of simultaneous export and investment booms, inflation was the rising

threat. US Treasury officials were not in so much of a shoving mood as in a mood of

concern. Even more worried were IMF staffers, who feared that a Canadian

revaluation would set a precedent and undermine the central exchange rate plank of

the Articles of Agreement. Rasminsky saw the problem, but he also now saw serious

design flaws in the structure of the Fund itself. His advice to the Minister of

Finance therefore took the following line. Especially after the formal end of

residual exchange controls, Canada should embrace its full obligations to the Fund

(so-called Article VIII status), but the Fund should be asked to acknowledge the

market conditions facing the country and quietly to exempt it from any obligation to

hold an explicit exchange rate peg or commit itself to reestablishing such a peg by

a certain date (Muirhead 1999, 143). This is exactly what happened. Fifty-three

years later, Rasminsky was forthright in his rationale for the policy he advocated:

"Our commitment to multilateralism mainly had to do with the desire to have a buffer

between us and the United States. Negotiating head to head with them was never

enjoyable. In a way, our position was like Switzerland's. An island of stability

and a great haven for capital flows in a turbulent world. It was often best to keep

our heads down."7

As Helleiner (2005) points out, the decision to float in 1950 was certainly backed

by the weight of opinion in the Canadian private sector. It would be an

exaggeration, however, to say that the actual decision to break Fund obligations and

float the currency originated there. Nor was there much evidence of any

particularly salient partisan influence or serious lobbying by provincial

governments. Not only did central governmental policy-makers value the final choice

of assigning priority to monetary autonomy and capital mobility, they themselves had

a significant amount of policy autonomy within the Canadian political system

actually to make such a choice. In a sense, the actual choice made by Canada's

small group of policy-makers could be seen as "ideational" or even ideological

(McNamara 1998). It seems more accurate, however, simply to call it logical, both in

light of market conditions and their understanding of the decentralized structure of

the Canadian state and the regionally differentiated nature of the national economy.

The only feasible alternative to floating the currency in 1950 would have been a

combination of very loose monetary policy, risking accelerated inflation during an

unexpected period of economic expansion, and the reimposition of capital controls.

Price stability was even then seen to be in the national interest, and so too was

the development of manufacturing in Quebec and Ontario and of commodity-based

businesses in the Maritimes and the West. Private American capital inflows were the

key. If this meant that bankers in Montreal and Toronto would have to continue

living with some hot money, this seemed a small price to pay. (I have seen no

record of loud objections emanating from that quarter.) Was currency speculation

ever really a serious problem? Rasminsky was clear: "No. We didn't build very

many long-term assets with short-term money."8

In light of such reasoning, the decision to re-peg in 1962 was anomalous. Unique

circumstances explain it, but in retrospect the main conclusion Canadian

policy-makers subsequently drew was that it was a mistake. Erratic domestic

economic policy in 1961 set the stage. A trade deficit was exacerbated by an overly

tight monetary policy that simultaneously depressed exports and attracted excessive

capital inflows. In the face of rising unemployment, a populist Conservative

government tried to talk the dollar down, the United States and the IMF began

complaining about competitive currency depreciation, and a politically tone-deaf

central bank governor refused to loosen the monetary reins. That governor, James

Coyne, was eventually fired and Rasminsky took his place. In addition to coming to

a formal understanding with the government concerning the responsibilities of the

Bank of Canada, Rasminsky's immediate task was to help restore confidence in a

Canadian economy beset by rising unemployment.

For a brief period of time, it seemed that one prudent way to do so would be to

accede to US and IMF calls to re-peg the exchange rate. Senior Finance Department

officials noted that there was some pressure from the business community to take

this route, but Rasminsky emphasized the need "to eliminate uncertainty" when, in

May 1962, he announced the decision to fix the rate (Plumptre 1977, 168; Muirhead

1999, 196). In later years, he also insisted that the government would never have

taken that decision if it had not believed that domestic circumstances themselves

had warranted it. In any event, it did not work. The rate immediately came under

pressure as a deteriorating trade position convinced the markets that the Canadian

dollar was overvalued. In order to defend the currency, the government found itself

forced into the classic posture of imposing fiscal stringency, raising interest

rates, and shoring up emergency reserves by borrowing from the Fund and the US and

UK central banks — all, again, in the face of rising unemployment. Once

committed, however, Rasminsky himself could see no other way out, except to urge the

government to take even more direct measures to reduce the current account deficit.

This necessarily implied reducing domestic production costs. He therefore urged

that "Cabinet should consult with business and labor." In the end, such

consultations could not quickly reduce those costs, and the government relied

instead on import surcharges. This antagonized the United States, but soon changed

market psychology. The exchange crisis eventually subsided; the focus of policy

attention shifted later in the decade away from unemployment and back toward

inflation.

By 1970, Canada faced again a situation very similar to that of 1950. Confidence in

the Canadian currency had long since returned; capital rolling now in from the

United States made alternative choices to re-floating the Canadian dollar

unpalatable. As Powell (1999, 49) puts it:

A defense of the [then] existing par value was untenable since it would require

massive foreign exchange intervention, which would be difficult to finance without

risking a monetary expansion that would exacerbate existing inflationary pressures.

A new higher par value was also rejected since it might invite further upward

speculative pressure, being seen by market participants as a first step rather than

a once-for-all change. The authorities also considered asking the United States to

reconsider Canada's exemption from the US Interest Equalization Tax. Application of

the tax to Canadian residents would have raised the cost of foreign borrowing and,

hence, would have dampened capital inflows. This too was rejected, however, because

of concerns that it would negatively affect borrowing in the United States by

provincial governments.

Even under the most aggressive pressure from American Treasury officials, especially

from Secretary John Connally, Canada refused to support the US attempt to shore up

the Bretton Woods system in the negotiations following President Nixon's decision to

suspend the official convertibility of the US dollar on 15 August 1971. Rasminsky

recalled the key negotiating session vividly:

Connally was very rude. We had to float, and I told him privately that we were not

his problem. We were not draining US gold reserves, since we were holding much of

our foreign reserve in the form of non-marketable T-bills. He began yelling about

Canada always having its hand out for one thing or another but never being willing

to help, and I raised my voice in anger. He stormed out of the room. In a public

session later, Connally asked [IMF Managing Director] Schweitzer if Canada was

contravening the Articles. He said yes. But we immediately intervened to ask

Schweitzer if he thought that under the circumstances it would be possible for

Canada to fix a durable par value. He said no. This probably helped put him in hot

water with Connally.9

After the Smithsonian Agreement was announced in December 1971, Canada's

unwillingness to participate in the re-pegging exercise was publicly and bluntly

attacked by Paul Volcker of the US Treasury and by Arthur Burns, then Chairmen of

the Federal Reserve. Canada, according to Burns in 1972, "had not been prepared to

be helpful to the USA in its time of need. (Muirhead 1999, 294)" Underlying Canada's

adamant position, however, was the reawakening of a strong preference for monetary

autonomy. The line of thinking was well articulated as early as 1932 by Clifford

Clark, arguably the country's most important deputy minister of finance ever and the

person who, along with central bank governor Graham Towers, originally recruited

Rasminsky to government service:

Under a policy of fixed exchanges, an upset in the country's balance of payments due

to a crop shortage, or a change in foreign demand for one or more of the country's

important products may have to be corrected by the painful process of restricting

credit and reducing prices and personal incomes. This process appears the more

ruthless when it is realized that many disequilibria in international balances of

payments are temporary in nature. The question may be raised whether the policy of

exchange stability in some cases does not involve the payment of too high a price

for the advantage gained…The arguments against a tie-up with New York and with

London constitute the case for retaining our national autonomy in monetary affairs

for the present at least. In particular, neither alternative offers any real

assurance of price stability or the restoration of our prices to a level at which

the burden of fixed debt upon the shoulders of industrialist and taxpayer will be

appreciably mitigated…If we retain our independence, we may choose our own

objectives and plot our own course towards them.10

What we might call the Clark-Rasminsky shared narrative on Canada's external

monetary and financial polices really extended from the 1930s straight through to

the 1990s and beyond. There has been no basic change in the country's exchange rate

regime since 1971, except for the even stronger commitment to floating represented

by a public understanding that the Bank of Canada would not intervene in foreign

exchange markets even to manage the rate. Such a commitment was harshly tested

during the 1990s, when the exchange rate plummeted to historic lows against the

dollar. To the surprise of many in the business community who continued to push the

cause of fixity, even to the point of monetary union, that commitment held

(Helleiner 2004). The strong recovery in the exchange rate in later years tested it

again from the opposite side. The Clark-Rasminsky consensus survives.

In sum, policy autonomy remains the key Canadian priority. In the wake of the

miserable experience of the 1930s and the shock to Canada's polity and economy posed

by World War II and the rapid erosion of the British Empire, there was a brief

moment when the country's monetary policy-makers were willing to consider new

international arrangements that might have fundamentally compromised that autonomy.

The need for an insulator might have been met by a radically new kind of

international organization. But by 1946, it was crystal clear that no such

organization could be created.11 The normal reaction of those actually charged

with managing Canadian policy quickly reasserted itself, in practice if not always

in rhetoric. The exchange rate would be the main instrument for buffering the

relationship between Canada and the only other economy that really mattered. Canada

wanted to be as helpful as possible in the establishment of the Bretton Woods

institutions. It would take them seriously, it would send respected senior

officials to sit on their boards. Even when it failed to meet the spirit of its

obligations to the Fund, it would go to great lengths before 1973 to ensure that the

Fund formally acceded to its "temporary" derogations. But even during the "golden

postwar era," it would always defend its own way of dealing with the practical

exigencies of external monetary and financial power. Its senior monetary officials

were pragmatic nationalists. Time and again, not wanting to impede the capital

inflows required to underwrite national prosperity nor to accept any serious

external constraints on monetary policy, they made the exchange rate the principal

buffer.

Ironically, the logic and consistent wisdom of this choice was starkly revealed when

Canada's monetary policy-makers made the mistake of re-pegging in 1962. Fearing the

consequences of quickly reversing course, they immediately confronted the core

political contradiction of the Canadian political economy. If external costs could

not be adjusted rapidly as payments pressures mounted, they would have to adjust

internal production costs. But they simply could not do so in a decentralized,

liberal market economy. The fact that the initial error was soon covered over by

the effects of an eventual inflationary boom in the United States in the 1960s

should not confuse the basic issue. In 1970, Canadian policy-makers once again

squarely confronted their internal political limits and reverted to their

traditional external practices. The exchange rate was the essential buffer, the one

capable of being deployed unilaterally and swiftly in a deadly serious game always

played on two dimensions. Internally, if business and labour could not be cajoled

into negotiated concessions to keep national production competitive, then a change

in the value of the currency could accomplish the same end less obtrusively, even if

internal regional effects might be unbalanced. Externally, the same kind of change

could shift some of the costs of adjustment onto others, or more benignly to limit

the shifting of such costs to Canada. Despite external political pressures

motivated by this reality, most prominently in the early 1970s, Canadian

policy-makers steadfastly refused to rely on any other policy mechanism. Blaming

financial markets for changes in living standards always proved a workable political

strategy, both internally and externally. It essentially managed the irresolvable

tension between continental economic integration and national political

independence.

Despite tremendous changes in the real economy of Canada since the 1970s, including

freer trade with the United States, the explicit adoption of inflation targeting in

1991, and dramatic fiscal restructuring in the mid-1990s, this logic continues to

hold.12 External shocks continue ultimately to entail abrupt changes in the

demand for Canadian goods and services, the composition of which varies markedly

across the country's regions. In the face of such shocks, one could certainly

imagine an alternative adjustment mechanism focused mainly on the movement of labour

or on relative changes in sectoral wages. But even in a post-NAFTA era, the

movement of labour across the Canada-US border is still more difficult and less

common than the movement of labour within the country, and it remains the case that

relative wages right across Canada's regions are sticky in nominal terms (Helliwell

1998).

The question of whether smoother and deeper continental adjustment will be possible

in the future is an open one, which overlaps with the quiet expert debate usually in

the background on the extent to which a separate currency now comes with mounting

transaction costs in markets Canadian policy-makers can rarely influence. Booming

cross-border trade and investment during the past decade suggest that such costs are

low, but the jury is out until more empirical work is done. The Clark-Rasminsky

consensus nevertheless continues to hold: as long as monetary policy is

disciplined, a flexible exchange rate facilitates macroeconomic adjustment and

stabilization in a continental economy, while simultaneously carving out a

relatively high degree of political autonomy for the Canadian state and the

decentralized national society it still seeks to steer.13

The Austrian Case

Austrians understand what it means to confront power. When the democratic Republic

of Austria was reconstituted on 27 April 1945, Germany had yet to surrender and the

country was occupied by the Soviet army. Allied troops were approaching from the

west, and their governments had yet to recognize the new state. Ironically,

although the country had been shattered by external forces more thoroughly than in

1918, the traumatic experience of the previous seven years effectively incubated a

new sense of national

identity. In a hostile environment, a new nation and a new

state initiated a complicated process of mutual construction. Especially after the

State Treaty of 1955 finally ended the Allied occupation, monetary policy became an

important instrument in that task. Where only 47 percent of its people considered

themselves to be members of an Austrian nation in the mid-1960s, within a quarter

century some 80 percent embraced just such an identity (

Riedlsperger 1991;

Katzenstein 1977). The performance of the Austrian economy, and of the schilling,

surely played no small part in this transformation. A small group of monetary

policy experts understood from the beginning the deeply political nature of their

own assignment. Like their Canadian counterparts, they may fairly be labeled

pragmatic nationalists, but their pragmatism led them in distinctly different

directions.

For those Austrian monetary policy-makers who remember the postwar atmosphere or who

remember what their forebears told them about it, two vivid impressions stand out.

The first is the pall cast over all discussions concerning money by the

hyperinflation of the early 1920s and by the way it ended, with the state in

receivership and the national financial accounts directly administered by a Dutch

national assigned by the League of Nations (Pauly 1997). The League commissioner

left in 1926, but by then the new Austrian National Bank was firmly established.

The law creating it on 24 November 1922 committed the Bank to one overriding

objective: safeguarding the stability of the currency. Even though the subsequent

fixed rate between the new schilling and gold had to be devalued by 28 percent at

the start of the Great Depression, support for a hard currency survived until German

troops were welcomed on 12 March 1938.

The fact that the Germans proceeded to loot the National Bank's reserves might have

been forgotten if the Second World War had turned out differently. But the memory

of that trauma among others was certainly useful to the builders of the Second

Republic. So too was the predictable postwar inflation. In rapid succession, the

resurrection of the Austrian National Bank, the reintroduction and devaluation of

the schilling, and the passage of the Currency Protection Act of November 1947

initiated a process of monetary stabilization.14 Underpinning the restoration of

monetary sovereignty was the first of five wage and price agreements between

organized Austrian industry and the national trade union association, the foundation

of the modern "social partnership," the heart of a coordinated market economy.

Bitter memories of debilitating industrial and class conflict during the inter-war

years framed that progressive-sounding but distinctively illiberal idea.15 Price

inflation was also in the background, and not just in people's memories. Not until

1952 did tightening monetary policies rein prices in. Exchange controls and a dual

exchange rate remained until the next year, when a one-time devaluation of the

schilling was matched with the declaration of a fixed link to the US dollar. On

this basis, Austria was able to join the IMF, and in 1958 to move with other

European states to a single exchange rate system and full currency convertibility.

By then, the social recommitment to the monetary orthodoxy of the late 1920s had

been tested and found durable. Despite the rebirth of passionate debates over the

famous Austrian black-red political divide, the base of support for price stability

remained broad and deep. It found expression in a 1955 act affirming the continuity

since 1922 of the National Bank and recommitting it to currency stability. Among

other things, the capacity of the Bank for independent action was widened through a

grant of powers to regulate the minimum reserves held by banks and to conduct open

market operations without prior approval from the government. This kind of central

bank "independence" in Austria, as elsewhere, is not as uncomplicated a notion as it

might at first appear.

If by the 1950s Austrians did not yet fully trust themselves to maintain a sense of

national solidarity for internal reasons, external conditions would provide

reinforcement. Social partnership meant that organized business groups, the

national farmers association, and workers ultimately organized under the peak

association of the trade union federation (ÖGB) would be authorized to make

national bargains. Once made, economic agreements in core sectors would effectively

apply to all participants in national markets, and those agreements would be

considered technically separate from ideological competition. Domestic politics, in

turn, would be guided by principles of federalism, proportional representation, and

the continual redivision of the spoils of power along red and black lines

(Proporzsystem).16 The fact that internal stabilizing measures had failed

catastrophically before 1938 undoubtedly contributed to a continuing sense of

vulnerability. But so too did the long shadow of the Soviet Union. Milivokevic

cuts quickly to the heart of the matter.

[The four power] occupation only ended when all the parties to the ten-year Austrian

deadlock agreed that the only possible and mutually acceptable status of a sovereign

Austria was permanent neutrality based on the Swiss model. Anything else would have

meant the formal partition of Austria…In deference to Austrian sensibilities, there

was no mention of permanent neutrality in the Austrian State Treaty of 15 May 1955,

although the precondition for the Soviet signing of this Treaty was unconditional

Austrian acceptance of permanent neutrality in the Moscow Memorandum of 15 April

1955…In the famous constitutional law of 26 October 1955, the Austrian government

formally proclaimed: "For the purpose of the permanent maintenance of her external

independence and for the purpose of the inviolability of her territory, Austria of

her own free will declares herewith her permanent neutrality, which she is resolved

to maintain and defend with all the means at her disposal. (Milivokevic 1990, 72;

also Cronin 1986)

But how to build up those means? History and geography pointed only one way:

economic interdependence with Germany, together with the construction of a robust

and distinctly Austrian identity. Katzenstein (1985) traces the delicate processes

through which Austrians went down precisely this road after 1955. But he spends

surprisingly little time on the monetary dimension of their crafting of the

institutional and then functional sinews of a secure nation. The necessity was to

find, and find quickly, non-military policy levers simultaneously to buffer the

power of former adversaries and the future power of a resurgent Germany: to take

the best from the outside world but to leave the rest. In this regard, where the

Canadians relied on a flexible exchange rate to accomplish such a task, the

Austrians consistently made the opposite choice.

During the delicate years after neutrality was proclaimed, the independent design of

Austria's fixed exchange rate regime was acceptable both to the Soviet Union and to

the Americans. Over time, such a regime proved stable because it tended to be

underpinned by anti-inflationary monetary policies. Most importantly, the essential

buffering mechanism necessitated by simultaneous preferences within Austria for both

economic openness and political autonomy was internalized.17 In short, a hard

currency was welded successfully to stable postwar social arrangements for

distributing internally the economic and political costs (and benefits) of gradually

opening the country once again to the world economy mainly through Germany.

Although political neutrality was an existential necessity for postwar Austria, the

practical priority was to recover and rebuild the economy as rapidly as possible.

Natural advantages and traditional networks reasserted themselves. Strong,

export-led growth was crucial, and for a land-locked country in the heart of central

Europe, diversification options were limited. The path reopened after the war would

lead within fifty years to an economy where trade would comprise over 60 percent of

GDP, nearly 40 percent of exports and imports would be to and from Germany (Italy

next at around 9 percent), trade in goods would result in a perennial deficit

requiring balancing receipts from services (like tourism) and investment.

Manufacturing, however, always played the central role in the strategy for recovery

and prosperity. Prevented by its neutrality commitment from joining the European

Community in its early days, few doubted the practical necessity of redeveloping

bilateral linkages with Germany in such industries as machine tools, chemicals,

metal goods, and steel. That basic idea certainly appealed to the labour unions in

what had always been a highly organized workforce. At its root lay the logical

necessity of keeping Austrian wages competitive with German wages. Logic is one

thing, however, and natural human impulses another. How to manage the trick? Enter

the exchange rate regime.

It is true that there was no automatic consensus on the notion of fixing the

bilateral Austrian/German rate at a level marginally favourable to the cause of

Austrian competitiveness. Certainly no one could talk of such things openly. For

one thing, German workers would not like to hear it. For another, after 1955 the

Russians were highly attentive to such matters and anything that sounded like

bilateral concertation sounded like a new "Anschluss" to them.18 Austrian

employer groups and industry leaders, moreover, were of two minds. They understood

the logic of bilateralism, but they also hoped to create options for export

diversification in the future. In this light, a flexible exchange rate, especially

a downwardly flexible one, could in principle be of considerable assistance.19

Along that latter line, even labour unions focused on Germany could be tempted by

the lure of devaluation.

During the 1960s, such matters were not so much the subject of academic disputation

as of practical experimentation. In 1961 and again in 1969, a broad revaluation of

the Deutsche mark on world markets seemed to present an opportunity. Recall that at

this time, the schilling was formally pegged to the dollar and did not automatically

follow the mark upwards. The social partners — business, labour, and

government — clearly hoped in each case that the opportunity would open new

markets for Austrian exports. What they experienced in fact was domestic inflation,

with real and palpable wage losses. Pensioners and others on fixed incomes spoke

darkly about the 1920s. Central bank officials eventually used the experience then

and now to teach a lesson about real effective exchange rates to all who would

listen. It seems doubtful, however, that such education can explain the depth of

the political commitment of both workers and bosses to a fixed exchange rate ever

since 1969. In any case, as Table 1 indicates,

afterwards only minor adjustments occurred in the nominal bilateral exchange rate.

Since the early 1980s the rate has been completely frozen (Winckler 1993). Those

final nominal changes are nevertheless worth more attention, for they marked the

point at which buffering mechanisms were deemed most clearly to be needed between

powerful economic forces and countervailing political exigencies.

Table 1: Austrian Schillings per German Mark

| 1955 | 6.19 |

| 1960 | 6.19 |

| 1965 | 6.48 |

| 1970 | 7.09 |

| 1975 | 7.08 |

| 1980 | 7.12 |

| 1985 | 7.03 |

| 1990 | 7.03 |

| 1995 | 7.03 |

No change since December 31, 1998, when the same nominal rate was converted to AS13.76 per euro.

Source: Austrian National Bank data.

Central bank officials from the 1960s recall the governor and the finance minister

spending considerable time with trade union officials, especially with the head of

the ÖGB, explaining the wisdom of a productivity-based wage policy. Such a policy

centered on the fixed link to the Deutsche mark (DM) and a follow-the-leader

strategy on both interest rates and labour costs. The beauty of the Bretton Woods

system was that no one had to be explicit about this. The excessive inflation

experienced after the DM revaluations in the later years of that system suggested

that Austria should simply have realigned in lock-step, a lesson union leaders were

willing to acknowledge. But the central bankers also recall confronting resistance

to this reasoning from business groups and the chancellor, as well as from the IMF.

From the Fund's point of view, Austria's structural trade deficit suggested then and

well into the 1970s the need for a devaluation of the schilling. The moment came to

square the political circle when the Bretton Woods arrangements finally began to

break down.

At one level, the 1971 devaluation of the dollar and the final decision to float in

1973 raised an obvious, awkward and politically sensitive problem. Inside Austria

an understanding had emerged among the social partners concerning the basic

industrial strategy decisively shaped by Austrian-German networks. The

straightforward monetary dimension of this reality before 1971 meant simply

importing low inflation from Germany via a fixed link between the DM and the dollar.

To the extent this may sometimes have necessitated flexibility in wages and

production costs inside Austria, the social partners stood ready to comply.20

As the dollar ceased to be a reliable anchor for that core relationship, however, it

initially proved impossible to shift to an explicit schilling-mark link. Two things

were at work. First, the Russians were still interested and still watching, and

even if they were not Austrian policy-makers were still absolutely convinced

otherwise (right through to the 1980s). Second, in its own deeply conflicted,

historically-conditioned way, Austrian nationalism was now a political fact. In the

ironic phrase of one former governor, this meant, and still means, Austrian policy

had to be one of "autonomous solidarity" with Germany.21 What this essentially

translated into in the early 1970s was tying the Austrian schilling explicitly to a

basket of European currencies while implicitly pegging it to the Deutsche mark.

Inside the central bank, considerable analytical resources were devoted to

calculating the basket rate on a daily basis and, whenever necessary to keep the

implicit peg rigid, to rejigging the basket. For Bank traders engaged in actual

open market operations, however, the task was uncomplicated. The target was

understood. For those who set Austrian interest rates, somewhat more delicacy was

required. Eventually, a standard practice emerged; the board would meet the same

day the Bundesbank board met; and whenever the Bundesbank changed its base rate, the

National Bank would within the hour "autonomously" decide to match it.

Only in 1975, in unusual political circumstances, was there a brief attempt to step

away from the post-Bretton Woods consensus by allowing a slight depreciation of the

schilling. Once again, certain business groups and trade union leaders were

apparently tempted by a strengthening mark to expand exports and secure an "extra"

wage increase, partly to compensate for price hikes occasioned by the Organization

of Petroleum Exporting Counties' (OPEC) continuing actions in world oil markets

(Winckler 1993). When the National Bank chose not to follow the Bundesbank in one

particular interest rate hike, a brief run on the schilling ensued, significant

reserves were lost, and accelerating inflation again followed. The lesson of money

illusion was re-learned, and the traditional consensus reasserted itself. One

central bank official recalls that in the year following this incident, the

chancellor for the first time explicitly defended the necessity of the fixed tie to

the Deutsche mark in talks with senior trade union officials.22

One final political struggle occurred in 1978-79, when the chancellor and the

finance minister took different sides on the question of how to restructure aging

industries like steel. The IMF and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and

Development (OECD), in particular, were quite critical of the excessive rigidity

introduced in this context by the DM peg. As one National Bank official explained,

"We knew that if we gave up the peg, it wouldn't have changed anything; we also

noted the experience of Norway and Sweden, for they had abandoned external

discipline but without positive results."23 In any event, the Bank briefly

delayed responding to one rise in German interest rates, a minor devaluation of the

schilling ensued, and the skeptics again proved right. Shortly thereafter, the

devaluation was reversed and the exchange rate rigidly (but unofficially) fixed at

7.03 schillings to the DM. When a similar controversy with the IMF occurred in

1991, the government and the central bank rejected outright the advice to loosen the

hard currency policy, and they even demanded a rewriting of the Fund's annual

performance assessment of the country.

Throughout the 1990s and until today, the hard-currency consensus remains dominant,

even if the success of the peg continue to be subject of some debate both externally

and internally.24 It certainly has made issues of fiscal adjustment more

difficult to avoid and contributed to recent political crises, especially associated

with the difficult challenge of pension reform.25 The rise of the Freedom Party

and its frontal attack on the social partnership system brought underlying tensions

to the fore in the mid-1990s. A few years later, however, one would be hard-pressed

to find evidence of dismantlement (Heinisch 2000).

The end of the Cold War, the 1994 move to join the European Union (EU), and the

subsequent decision to become a founding member of European Monetary Union (EMU)

opened a new chapter in this continuing story. On one level, there is no puzzle

surrounding the ease with which the schilling followed the mark into EMU. The fixed

link of both currencies to the euro simply replaced a bilateral connection. On

another level, however, a subtle but important change was involved.

The history of Austria's efforts to move beyond the dogma of neutrality as the Cold

War was ending and European integration was deepening and broadening is a

fascinating subject, but one which goes beyond the scope of this paper. For present

purposes, it is just necessary to note the clear-eyed perception of Austrian

monetary policy-makers as they oversaw the transition from the era of the hard

schilling to the era of the euro. At base, the move meant abandoning a reliable but

relatively passive set of policy practices. After the euro was adopted, the notion

of "autonomous solidarity" with Germany became less of an ironic turn of phrase. By

joining EMU, Austria now gained meaningful voice in the making of the monetary

policy it now explicitly shared with Germany and other European partners.26 To be

sure, the volume of the Austrian voice would not match that of Germany or France in

the arcane processes through which European monetary policy would be set. But

Austria had no voice in the Bundesbank when it used to matter, and it now did indeed

have a voice when the European Central Bank was decisive. Through EMU Austria was

able to maintain its hard currency policy in relation to Germany. It also now had

two buffering mechanisms as it confronted external markets and the raw monetary and

financial power of Germany and others: a cooperative multilateral institution of

which it was now an intimate part and a continuing internal capacity to match

changes in German production costs.27

Conclusion

"Trust, but verify," Ronald Reagan famously advised Americans when they sought new

arms control arrangements with the Soviet Union in the 1980s. If he had been a

monetary policy-maker in Canada or Austria any time since 1945, he may similarly

have opined, "Cooperate, but maintain room for maneuver." As in other arenas of

power, neither Canada nor Austria ever really wanted to challenge the international

monetary policies of the leading states on their borders. But those policies

affected them and could not be ignored. Their states wanted to get as much as they

could for their societies from multi-faceted economic relationships, but they also

sought to build and maintain separate nations.

28 To accomplish their objectives,

carving out as much practical autonomy as possible was the critical task. In

essence, this meant crafting institutional and policy buffers, the operation of

which could be at their own discretion. There were limits to international monetary

power, and they would define those limits for themselves.

In the face of such follower strategies, what was left for the leaders?

Acquiescence, when they were wisely led. Purposeless confrontation, when they were

not. It is often claimed that it is the willing acquiescence of followers that

transforms coercive power into authoritative leadership. In the two special

relationships explored in this paper, however, acquiescence by leaders to the

existence and use of effective buffers was the wise response. Coercive attempts to

make the follower change strategic tracks, for example, most overtly in the 1971

US-Canada dispute, failed.

Across the Canadian and Austrian cases, it is not the existence of buffers in the

crucial bilateral currency relationship that varies but their character, which

appears functionally related to the deeper historical trajectory of their internal

political economies. In both cases at particular times, windows opened on the

possibility of serious participation in truly multilateral institutions that just

might substitute for other buffering mechanisms. Only very recently in the

German-Austrian case, did such a choice seem partially to satisfy the needs of the

follower state. In terms of effectively responding to an insistence on a voice in

making shared monetary policies, the European Central Bank (ECB) may satisfy Austria

in a way not dissimilar from the way Rasminsky once hoped a Keynesian Currency Union

might satisfy Canada. Austria may be said, therefore, to wield in institutional

terms somewhat more external monetary influence, if not power, than Canada does. In

the end, however, it remains doubtful that cooperative multilateral mechanisms have

convinced many people in either country that they should be relied upon as the

ultimate political buffers. Austria and Canada both retain their own central banks,

and both continue, each in their own ways, tenaciously to defend their room for

maneuver in the context of integrating regional economies.

In the Canadian case, the final buffer in the monetary arena would always be a

flexible exchange rate. Only once was another briefly imagined. When Rasminsky

advised the federal Cabinet to consult with business and labour groups on measures

to support a re-pegged exchange rate, he meant coordinated measures to render

domestic prices and wages downwardly flexible. This was a pipedream. Canadian

society lacks the sense of solidarity and social cohesion either to design or to

implement such measures. "The ideology of social partnership" has no counterpart in

liberal Canada. But neither does the alternative ideology of "neo-liberalism"

resonate deeply in a dualistic nation built across diverse regions. Since 1945, a

flexible exchange rate has been the key political instrument available to the

Canadian state. It is the one instrument under national control that can limit the

capacity of the Americans to export the costs of bilateral adjustment. It is also

the one instrument the state has at its disposal to ameliorate adjustment burdens

generated within Canada and to redistribute them across a fractious society. Even

if certain mobile factors of production could avoid taking their full share of such

burdens, there was no substitute for the flexible exchange rates as Canadians

collectively sought maximal gains from increasingly integrated continental markets.

That particular buffer made it possible to follow the leader on their own terms.

Austria could have pursued a similar course over the decades since World War II.

Certainly many Canadian economists would have expected them to do so, as did the

IMF. At times, even industrialists within Austria advocated exchange rate

flexibility. Actual experience suggested otherwise. Useful for those advocating a

hard currency policy were memories of the 1920s, but especially important was a

remarkably enduring social consensus on the wisdom of keeping inflation low to

ensure that Austrian production costs would always marginally undercut competing

German costs. Still, such a consensus would have meant little in the absence of

workable political mechanisms for rendering real prices and wages within Austria

seriously flexible when circumstances so required. The social partnership system

born in the bloody class conflict of the interwar period proved robust enough for

this purpose throughout the postwar era. Some skeptical observers now argue that

the country's coordinated market economy is under serious threat, as the necessity

of pension reform and rising regional demands push it to the breaking point. Such a

contention remains doubtful, at least with respect to monetary policy, and it

downplays the historical success of implicit flexibility within Austria's

coordinated market economy. Capitalism continues to manifest variety in both its

internal and external dimensions.

It may be true that only follower states in the advanced industrial core can now

craft, defend, and use such buffers at the interface of their societies and

international markets. There is, however, no reason to accept the assertion that

globalizing markets now render autonomy impossible for all but a few. As the

Canadian and Austrian exchange rate cases suggest, diverse national strategies

remain possible and specific policy choices may reflect internal political and

social arrangements more than external economic constraints.

Acknowledgement

Early versions of this paper were presented at the annual meeting of the

International Studies Association, 17-20 March 2004 and at the European University

Institute, 16 May 2004. For constructive comments, I am grateful to David Andrews,

Stephen Harris, Beth Simmons, and Bob Hancké. For generously sharing original

empirical material on the two main cases, I am deeply indebted to David and to Eric

Helleiner. Eduard Hochreiter, Georg Winckler, and Aurel Schubert proved of great

assistance in Vienna. In Ottawa, during his last years, Louis Rasminsky graciously

shared his recollections. Financial assistance came from the Social Sciences and

Humanities Research Council of Canada and from the Robert Schuman Centre for

Advanced Studies. A revised version of this paper will be published as a chapter in

International Monetary Power, edited by David Andrews, Ithaca, NY: Cornell

University Press, forthcoming.

Works Cited

Abdelal, Rawi. 1998. The politics of monetary leadership and followership: Stability in the European monetary system since the currency crisis of 1992. Political Studies 46:

236-59.

Andrews, David, C. Randall Henning, and Louis Pauly. eds. 2002. Governing the world's money. Ithaca:

Cornell University Press.

Breuilly, John. 2002. Austria, Prussia and Germany 1806-1871. London:

Longman.

Clarkson, Stephen. 2002. Uncle Sam and us. Toronto:

University of Toronto Press.

Cohen, Benjamin J. 1983. Balance-of-payments financing: Evolution of a regime. In International regimes,

ed. Stephen Krasner,

457-78. Ithaca:

Cornell University Press.

Cohen, Benjamin J. 1998. The geography of money. Ithaca:

Cornell University Press.

Cohen, Benjamin J. 2004. The future of money. Princeton, NJ:

Princeton University Press.

Cooper, Andrew, Richard Higgott, and Kim Nossal. 2004. Relocating middle powers: Australia and Canada in a changing world. Vancouver, BC:

UBC Press.

Cronin, Audrey. 2004. Great power politics and the struggle over Austria, 1945-1955. Ithaca:

Cornell University Press.

Frieden, Jeffrey. 1996. Economic integration and the politics of monetary policy in the United States. In Internationalization and domestic politics,

ed. Robert Keohane and Helen Milner,

108-36. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Fullerton, Douglas. 1986. Graham Towers and his times. Toronto:

McClelland and Stewart.

Grande, Edgar and Louis W. Pauly. eds. 2005. Complex sovereignty: Reconstituting political authority in the twenty-first century. Toronto:

University of Toronto Press.

Hall, Peter and David Soskice. 2001. Varieties of capitalism. Oxford:

Oxford University Press.

Hancké, Bob and David Soskice. 2003. The political economy of EMU: Political exchange, wage setting, and macro-economic policy. In Final report for project 2000-203-1, Institutionen, Wirtschaftswachtum, und Beschäftigung in der EWU. Berlin, Germany:

Wissenschaftszentrum.

Heinisch, Reinhard. 2000. Coping with economic integration: Corporatist strategies in Germany and Austria in the 1990s. West European Politics 23

(July):

67-96.

Helleiner, Eric. 2003. The making of national money: Territorial currencies in historical perspective. Ithaca:

Cornell University Press.

Helleiner, Eric. 2004. The strange politics of Canada's NAMU debate. Studies in Political Economy 72

(Winter):

567-89.

Helleiner, Eric. 2005. A fixation with floating: The politics of Canada's exchange rate regime. Canadian Journal of Political Science 38

(1):

1-22.

Helliwell, John F. 1998. How much do national borders matter? Washington, DC:

Brookings Institution.

Henning, C. Randall. 1994. Currencies and politics in the United States, Germany, and Japan. Washington, DC:

Institute for International Economics.

Holmes, John. 1981. Life with uncle: The Canadian-American relationship. Toronto:

University of Toronto Press.

Kaelberer, Matthias. 2004. The euro and the European identity: Symbols, power, and the politics of European monetary union. Review of International Studies 30:

161-78.

Katzenstein, Peter. 1977. The last old nation: Austrian national consciousness since 1945. Comparative Politics 9

(2):

147-71.

Katzenstein, Peter. 1984. Corporatism and change. Ithaca:

Cornell University Press.

Katzenstein, Peter. 1985. Small states in world markets. Ithaca:

Cornell University Press.

Katzenstein, Peter. 2003. Small states and small states revisited. New Political Economy 8:

9-30.

Keohane, Robert S. and Joseph S. Nye. 1977. Power and interdependence: World politics in transition. Boston:

Little, Brown.

Kirshner, Jonathan. 1995. Currency and coercion. Princeton, NJ:

Princeton University Press.

Kirshner, Jonathan. ed. 2003. Monetary orders: Ambiguous economics, ubiquitous politics. Ithaca:

Cornell University Press.

Kitschelt, Herbert, Peter Lange, Gary Marks et al. eds. 1999. Continuity and change in contemporary capitalism. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

McNamara, Kathleen. 1998. The currency of ideas. Ithaca:

Cornell University Pres.

Milivokevic, Marko. 1990. Neighbours in neutrality: Aspects of a close but delicate relationship. Journal of Politics and Society in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland 3

(1):

69-83.

Muirhead, Bruce. 1999. Against the odds: The public life and times of Louis Rasminsky. Toronto:

University of Toronto Press.

Pauly, Louis W. 1997. Who elected the bankers? Surveillance and control in the world economy. Ithaca, New York, and London:

Cornell University Press.

Pauly, Louis. 2003. Canada in a new North America. In The rebordering of North America,

ed. P. Andreas and T. Biersteker,

90-109. New York:

Routledge.

Pichelmann, Karl and Helmut Hofer. 1999. Austria: Long-term success through social partnership. London:

International Labor Organization Employment and Training Papers, No 51.

Plumptre, A.F.W. 1977. Three decades of decision: Canada and the world monetary system, 1944-75. Toronto:

McClelland and Stewart.

Powell, James. 1999. A history of the Canadian dollar. Ottawa:

Bank of Canada.

Riedlsperger, Max. 1991. Austria: A question of national identity. Journal of Politics and Society in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland 4

(Autumn):

56-62.

Rothbacher, Albert. 1995. EU accession and political change in Austria. Revue d'Intégration Européene 19/1

(Autumn):

71-90.

Scharpf, Fritz and Vivien Schmidt. 2001. Welfare and work in the open economy. Volumes 1 and 2. Oxford:

Oxford University Press.

Schembri, Lawrence. 2003. Exchange rate policy in Canada: Lessons from the past, implications for the future. Britain and Canada and their Large Neighbouring Monetary Unions, University of Victoria, 17-18 Octob.

Schmidt, Vivien. 2002. The futures of European capitalism. Oxford:

Oxford University Press.

Simmons, Beth A. 1994. Who adjusts? Domestic sources of foreign economic policy during the inter-war years. Princeton:

Princeton University Press.

von Riekhoff, Harald and Hanspeter Neuhold. eds. 1993. Unequal partners. Boulder, CO:

Westview.

Winckler, G. 1993. The impact of the economy of the FRG on the economy of Austria. In Unequal partners: A comparative analysis of relations between Austria and the Federal Republic of German and between Canada and the United States,

ed. Riekhoff and H. Neuhold,

154-68. Boulder, CO:

Westview Press.

Wonnacott, Paul. 1965. The Canadian dollar, 1948-62. Toronto:

University of Toronto Press.

Notes

1.

The trailblazer here is von Riekhoff and Neuhold (1993). The volume includes a

few paragraphs on Austria's exchange rate policy by the distinguished economist

Georg Winckler, but practically nothing on the Canadian comparator.

2.

Katzenstein's directly relevant insight concerning successful small states in a

globalizing economy is that their economic policies are shaped by broadly shared

perceptions of vulnerability, by social learning, and by attendant efforts to

construct effective tools for defending their national interests (Katzenstein 1984;

1985; 2003).

3.

On the concepts of leadership and followership in this arena, see Abdelal (1998). On the underlying concepts applied in a broad comparison involving Canada, see Cooper, Higgott, and Nossal (1993).

4.

Interview, Ottawa, 11 August 1993.

5.

Ibid.

6.

Ibid.

7.

Ibid.

8.

Ibid.

9.

Interview, Ottawa, 1 August 1993. Also see Muirhead (1999, 293).

10.

Clark, W.C. 1932. Monetary Reconstruction, National Archives of Canada, RG25 D1 v. 770 File 333, 145-46, 195, quoted in Helleiner (2005).

11.

Rasminsky had spent most of the 1930s working in the economic and financial

department of the League of Nations. In the twilight of his life, he concluded that

although Keynes' more ambitious plans for a currency union remained noteworthy, the

creation of the IMF actually did represent something new. He felt it was wrong to

underestimate its role in postwar history. "What emerged was better than the

League, and probably as much as the United States could ever stomach politically.

The decisions made in Savannah in 1946 were bad ones, but Congress and the

politicized environment in Washington likely made them unavoidable. In the end, the

Fund can claim substantial credit for the prosperity of the golden age of

1945-1970." Interview, Ottawa, 11 August 1993.

12.

Stephen Harris, once a senior official in the Bank of Canada, emphasizes that

inflation targeting became especially attractive to Canada after the difficult era

of rising prices and high interest rates in the late 1980s. In its aftermath,

dominant thinking in the Bank held that if Canadian inflation performance could

better that of the United States, interest rates could be made-in-Canada. Hard

experience in the 1990s and beyond undercut this reasoning. Personal

correspondence, 31 March 2004.

13.

For an exceptionally clear statement of this position and of the associated

agenda for future research, see Schembri (2003).

14.

See Austrian National Bank website. Österreichische Geldgeschichte,

www.oenb.at (accessed 1 June 2005).

15.

Katzenstein (1984, 28-29) traces its roots to nineteenth century nationality

conflicts in the multi-ethnic Austro-Hungarian Empire and the syndicalism of

Austro-Marxism. Add to that the social teachings of Christian democracy in the late