The constant gardener

AIDS Pandemic

Nancy A. Johnson,

McMaster University

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) and, more recently, Avian flu have raised alarm about how globalization can accelerate the spread of deadly diseases, and have demonstrated the effect that the threat alone of a pandemic can have on global markets. They have also demonstrated the response of national governments and cooperation of international bodies, such as the World Health Organization, in preparing for and managing the early stages of possible pandemics. SARS, in particular, jolted Canadians' awareness of how transnational travel can, overnight, land an emerging viral threat from one side of the world on the tarmac of an airport on its other side. While increasing movements of people play a role in the spread of HIV/AIDS, globalizing processes have also led to cultural, social, and economic changes in many societies which can impact adversely on the health of individuals and populations. Some of these changes include armed conflict and political upheaval, disruption of rural community life, migration to cities, unemployment, and increased poverty. These changes can accelerate the risk of HIV transmission by bringing people into greater contact with one another, thus increasing risk of exposure to the virus. They also create or contribute to circumstances that limit peoples' capacity to respond to risk as well as their ability to seek care, obtain medications, and comply with treatment once they have become infected.

AIDS (Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome) is a severe disorder of the immune system caused by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). The illness progresses through a series of stages marked by a successive decline in the immune system's ability to protect the body and increasingly serious and more frequent opportunistic infections. HIV is spread by sexual contact with an infected person, by sharing infected needles or syringes (usually for drug injection), or through transfusions of infected blood or blood clotting factors. Babies born to HIV-infected women may become infected before or during birth or through breastfeeding after birth. Treatment of HIV patients involves a combination of antiretroviral drugs to slow the virus' progression, along with medications intended to prevent the diseases that develop when a person's immune system has been damaged by the virus. Despite the success of these treatments over the past decade in prolonging and improving the quality of life for people living with HIV, there is no known cure for AIDS. Prevention is, thus, an important part of local and global public health efforts to curtail the spread of the AIDS.

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) estimates that, in 2005, 40 million people worldwide were living with HIV. An estimated 4.1 million people became newly infected with the virus and 2.8 million people lost their lives to AIDS (UNAIDS 2006). Diagnosed on every continent but Antarctica and in virtually every country, AIDS is called a "pandemic" (an epidemic that touches all parts of the world). Although AIDS is a global health problem, it looks different in different parts of the world, in terms of numbers of people living with HIV, trends in incidence rates (new infections as a proportion of uninfected persons), principal means by which the virus is transmitted, the types of opportunistic infections to which victims frequently succumb, as well as the mix of social and economic factors influencing both transmission rates and the burden presented by the disease.

|

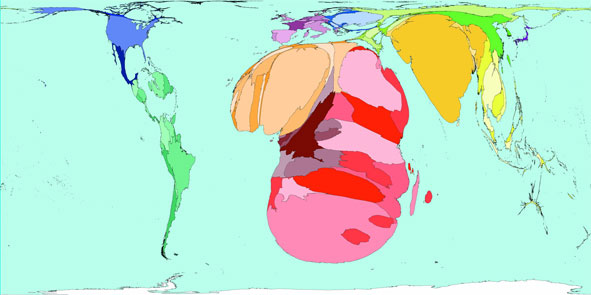

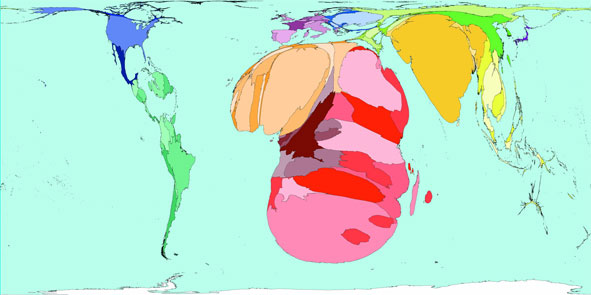

| HIV Prevalence in 2003 (Territory size shows the proportion of all people aged 15-49 with HIV worldwide, living there) |

(© Copyright 2006 SASI Group (University of Sheffield) and Mark Newman (University of Michigan))

The burden of HIV/AIDS on individuals, households, health care systems, and economies is enormous. This burden is not evenly shared. More than 95 percent of the people with HIV/AIDS live in the developing world (UNFPA website). In sub-Saharan Africa alone, despite a recent UNAIDS report (2006) that incidence rates appear to be stabilizing, more than a quarter of the adult population is infected. Within developed countries, HIV rates are highest among poorer populations. In the United States infection rates are rising among poorer black and Hispanic populations. In Canada, the pandemic has had a disproportionate effect on indigenous peoples who represent just over 3 percent of the population but comprise 6-12 percent of new HIV infections (UNAIDS 2006). The burden is also borne most heavily by women and children and by individuals or groups at the margins of society, including illegal immigrants, transient workers, people displaced by conflict or humanitarian crisis, commercial sex workers, prisoners, injection drug users, transsexuals, and men who have sex with men.

HIV/AIDS thus presents a different visual image of the spatio-temporal spread of epidemics than the one we perhaps hold in our heads of a wave spreading steadily and evenly outward across a level landscape. The spread of HIV/AIDS is more like water released from a dam, quickly flowing away from its source, seeking out and following the fissures of poverty, gender inequality, and social exclusion.

Often those individuals or groups who are most vulnerable to HIV/AIDS are those whose autonomy is most fragile or is circumscribed by the social, cultural, political, and economic realities of their day-to-day lives. One inescapable reality is gender. For reasons of culture, marital status, poverty, or religious belief/proscription, women are often unable to negotiate safer sex. Indeed, where violence or fear determine when sex occurs, negotiation never enters the picture and personal autonomy is violated in the most extreme way. Rape and coercion of sex in exchange for food, employment, shelter, or protection are faced by both male and female commercial sex workers, illegal immigrants, prisoners, and refugees.

Poverty, unemployment, loss of livelihood, and lack of education can force individuals and households to make difficult and sometimes desperate choices that place them at greater risk for HIV infection. Poverty may compel women or girls to exchange sex for food or money to feed their families. Men may travel long distances from home to find work. HIV/AIDS spreads rapidly in the context of migrant labour. Away from spouses or partners for long periods of time, men may engage in casual sex with a series of partners, or seek out commercial sex workers. Recent reports from China indicate a growing rate of HIV infection among the poor who have sold their blood at illegal clinics where infected syringes are reused. Lack of money and social stigma may prevent individuals from seeking health care. Poverty, social alienation, and despair fuel high rates of injection-drug use, which in turn fuel high rates of HIV/AIDS transmission.

To the extent that globalization may increase poverty, conflict, social dislocation, migration, urbanization, and human rights abuses — all of which influence population- and individual-level health risk — it can be seen to play a negative role in the AIDS epidemic. This role tends to be overshadowed in current discussions of globalization, health, and autonomy which focus more on global trade rules and national autonomy (for example, the WTO Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights and pharmaceutical prices) or the effects of trade liberalization on the availability of resources for public expenditure on health. Understanding the linkages between globalization and individual or population health risk underscores the need for health policies and initiatives aimed at empowering individuals and communities, expanding choices, promoting human rights, and addressing structural issues that create inequities.

Works Cited:

UNAIDS. 2006.

2006 Report on the global AIDS epidemic. Geneva:

UNAIDS.

Available:

http://www.unaids.org/en/

(accessed 9 June 2006)

Suggested Readings:

AVERT website.

www.avert.org (accessed 9 June 2006).

Lewis, Stephen. 2005.

Race against time. Toronto:

Anansi.

Marmot, Michael. 2005. Social determinants of health inequities.

Lancet 365:

1099-1104.

Available:

http://www.who.int/social_determinants/strategy/en/Marmot-Social%20determinants%20of%20health%20inqualities.pdf

(accessed 9 June 2006)

UNAIDS website.

www.unaids.org (accessed 9 June 2006).

Woodward, D., Drager, N., Beaglehole, R. and Lipson, D. 2001. Globalization and health: A framework for analysis and action.

Bulletin of the World Health Organization 79:

875-81.

Available:

http://www.scielosp.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0042-96862001000900014&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=en

(accessed 9 June 2006)

Worldmapper website.

www.worldmapper.org (accessed 7 February 2007)